In the early years of the twentieth century, Western nations embraced an invention that was to revolutionize land transport: the automobile. By the end of the 1920s, the car not only would have brought mobility to millions but also would have changed the face of society.

The key to the car's success was internal combustion, a principle understood in its crudest expression since the firing of the first gun. Not until the late nineteenth century, however, was the confined force of an explosion—produced by the ignition of such substances as petroleum or benzene— widely harnessed as a means of locomotive power. By 1900, following the work of German pioneers Carl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler, engineers worldwide were producing gasoline-driven road vehicles, dubbed horseless carriages.

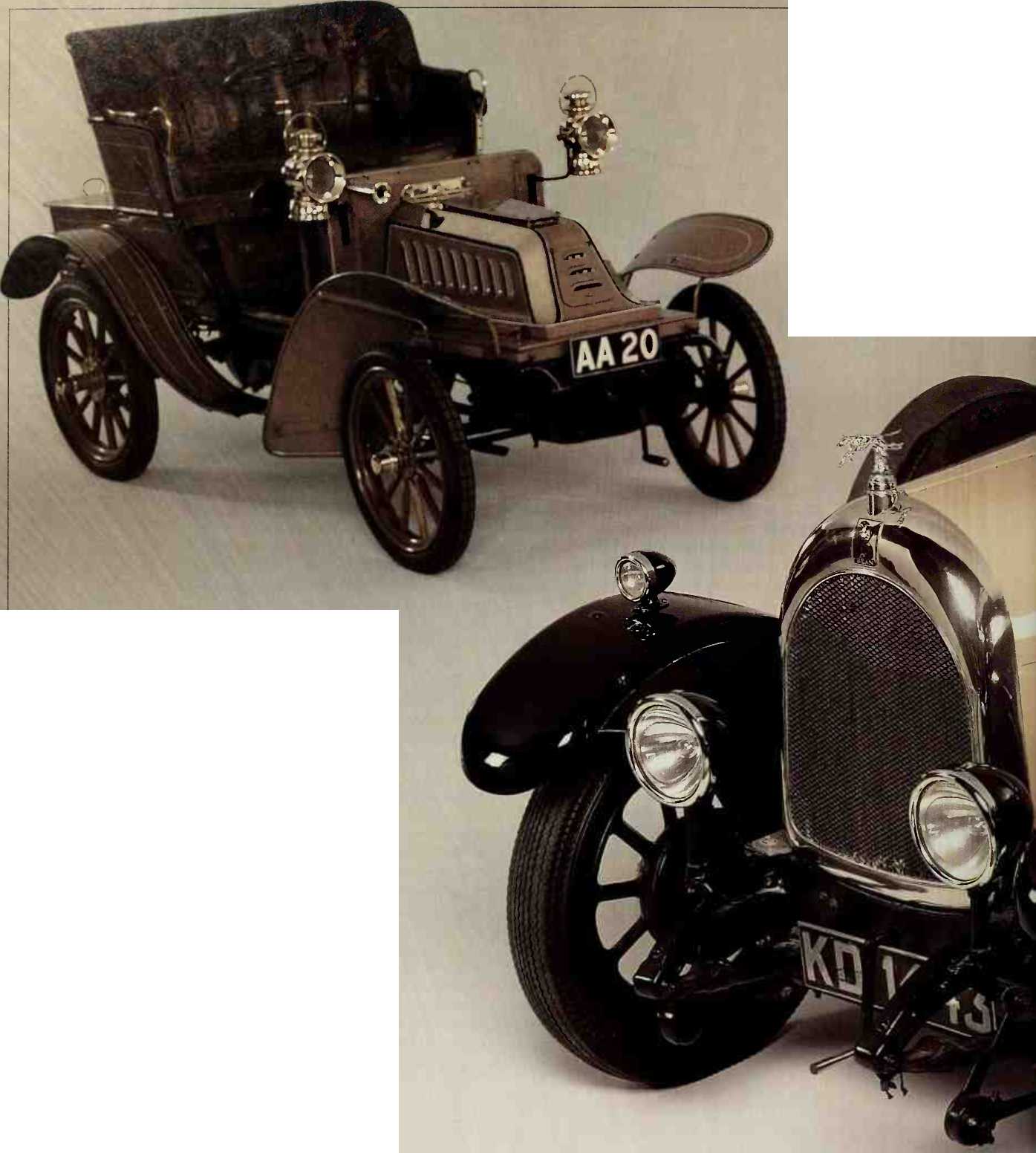

These early cars—affordable only to the wealthy—vibrated uncomfortably and were unreliable, noisy, and slow (the 1897 Benz, above, could manage only eighteen miles per hour). Nevertheless, they were more biddable than horses, and compared with steam engines and their attendant fire hazards, or with electric vehicles and their bulky, short-lived accumulators, they were paragons of mobility.

As the twentieth century progressed, cars became more sophisticated and more widely available. Mass-production techniques, perfected by the American manufacturer Henry Ford in 1913, set prices on a downward spiral that brought cars to an ever-wider market. And the use of motorized vehicles in the Great War boosted production still further, while accelerating technological advance: Superchargers, for example, developed by wartime aeroengi-neers to increase engine power, were later adopted by the auto industry.

At the same time, war familiarized people with the car, and many servicemen returned home in 1919 eager to acquire their own vehicles. Bereft of war work, factories hastily regeared to meet the demand, and in the affluent 1920s, automobile production soared around the world. The epicenter of this increase was in the United States. The 2.5 million cars on American roads in 1915 had become 27 million by 1929, by which time motorized transportation had substantially affected the way people lived. In answer to a comment that her family owned a car but no bathtub, one American housewife replied, "Why, you can't go to town in a bathtub!" The world had entered the Age of the Automobile.

A POLISHED PRODUCT

Most early cars, including this 1903 De Dion Bouton, had no roof or windshield; passengers donned caps, goggles, face masks, and gloves to protect themselves from the elements and from the dust their cars stirred up. The car's small lamps ran on oil rather than on electric current. Since most roads did not have streetlights at the time, even this meager light source lessened the hazards of night travel.

The early "horseless carriages" proved worrisome status symbols to their wealthy owners. The engine, mounted on a traditionally styled carriage, had to be coaxed into life by turning a hand crank or by pulling on a flywheel; primitive controls meant that changing gears was no mean feat; and solid rubber tires made travel a bone-jarring experience.

Automobile manufacturers, drawn from occupations as diverse as electrical engineering and bicycle making, were quick to work on the problems. Inflatable tires were one advancement, and by the 1920s, shock absorbers helped smooth the ride even more. Improved gear systems and the electric starter reduced the amount of brute force required for motoring.

Amid the technological progress, traditional coach-building skills were not forgotten. Many firms made only the mechanical components, and then referred buyers to craftsmen who would custom-build the body. Clients could request such costly extras as ostrich-hide upholstery and rosewood dashboards.

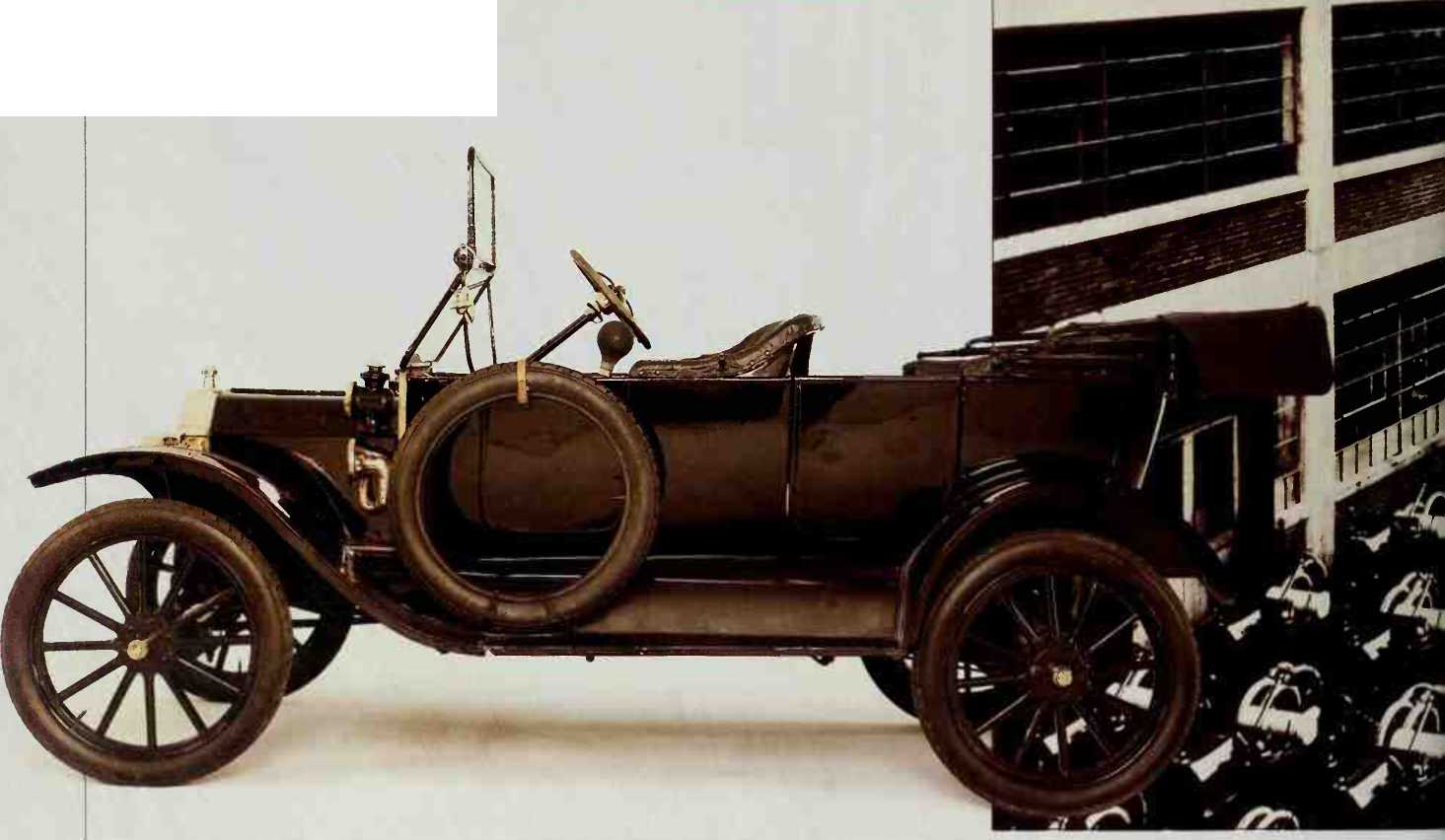

The bodywork of this English sedan, a 1928 Bean Short 14, shows that by the 1920s, automobiles were no longer simply playthings for fine-weather excursions but were now integrated into everyday life. This Bean had a top speed of fifty-five miles per hour; nevertheless, as the toolbox on the running board testifies, maintenance and adjustment were frequent chores.

THE CONVEYOR-BELT CAR

In 1903, Henry Ford decided to “build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be constructed of the best materials ... after the simplest designs... but it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one." His dream came true in 1908 when the Ford Motor Company produced the first Model T.

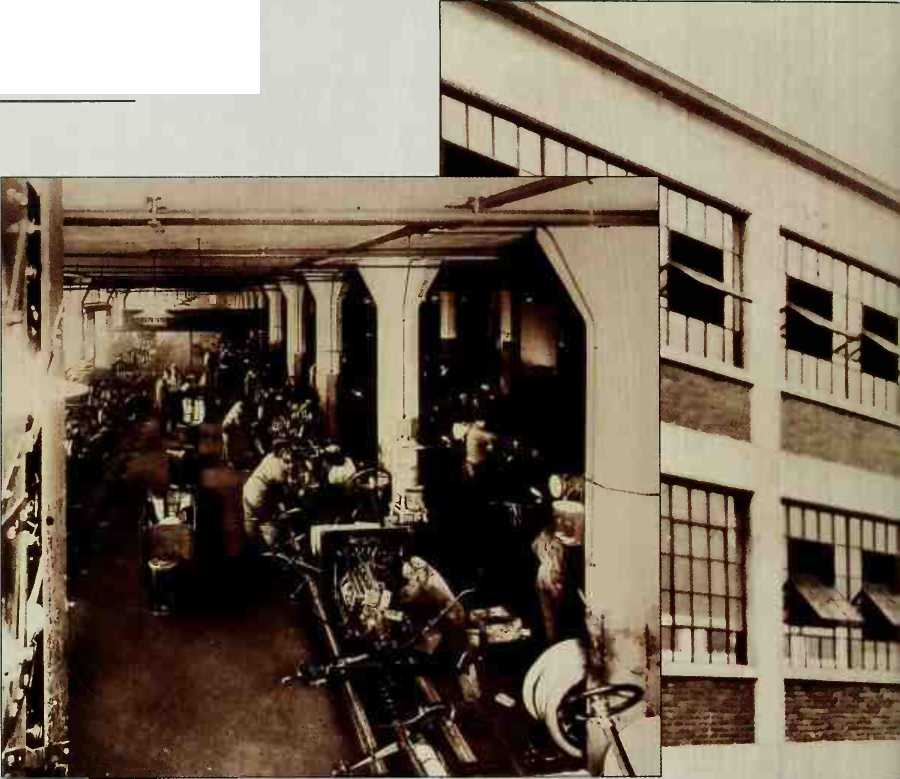

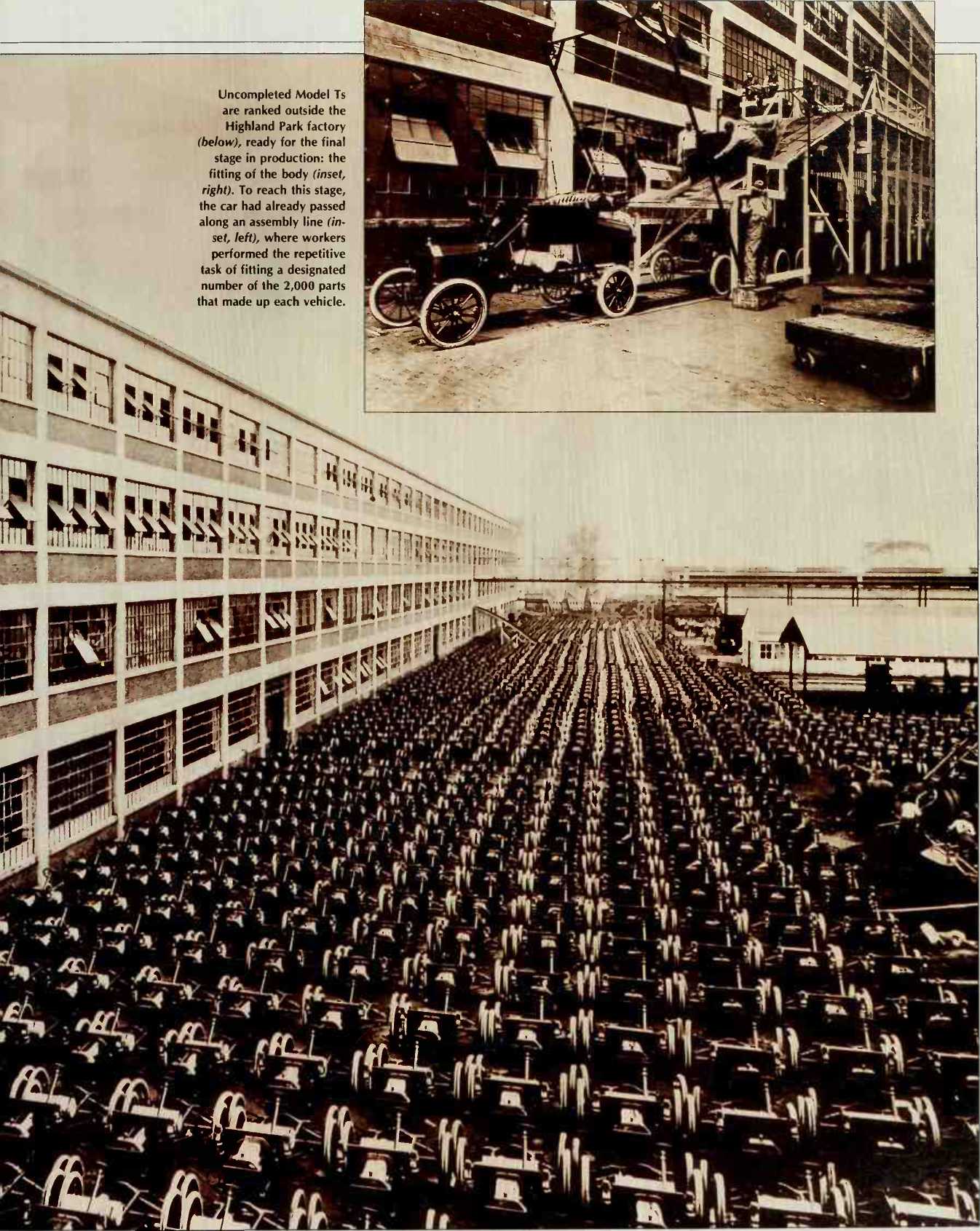

Durable, simple, and easy to repair, the Model T was instantly popular. Its success was assured in 1913, when Ford introduced the world's first moving assembly line at his Highland Park factory in Detroit, Michigan. By 1914, a Model T was rolling off the line every forty seconds; and the savings of mass production were such that Ford undercut his competitors by 60 percent and still paid his workers double the going rate.

Everyone loved the Tin Lizzie, as the rugged machine became known. The rear seats could be removed to turn it into a truck; chemical tanks and hoses could be fitted for firefighting; and one enterprising evangelist even converted his vehicle into a mobile church. In 1927, when production ceased, 16 million Model Ts had been sold worldwide; not until the early 1970s would that record be broken.

World History

World History