The day after docking in Cardiff, the contingent headed for London. The long train journey revealed not only England’s rural beauty, but also some of her wartime strategies. New airfields and factories had been sited throughout the countryside to reduce target potential and minimise damage such as London had suffered.

The young airmen arrived late in the blacked-out capital and it was not until morning that they were confronted with the scars of the Blitz. Seeing the skeletons and shells of buildings, and other sites razed to the ground, shocked them.

‘Jerry sure has been busy!’ they exclaimed.

‘And that’s what we’re going to be doing to Jerryville!’ they thought.

Looking eagerly from the bus taking them to their next train, David was agog at the postcard images he recognised as they drove - Nelson on his column flanked by lions in Trafalgar Square, under Admiralty Arch following the

Big Ben, Westminster, in wartime London (AWM neg. no. 002752)

Route of royal processions along The Mall, past St James’s Palace and Buckingham Palace, where the Royal Standard proudly flew, to arrive at Victoria Station. So different from Australian stations. Not as impressive outside as Melbourne’s Flinders Street, but its interior loftier and more extensive, home to multitudinous pigeons which scurried among the feet of the myriads of hurrying passengers.

David had always revelled in English history and literature so he was eager to see for himself the country that inspired England’s great poets. As the electric train sped through Surrey and Sussex meadows, woods and downlands, he delighted as more of William Blake’s green and pleasant land unfolded. They were headed to the famous seaside town of Brighton, 50 miles from London, where the once-crowded shingly beaches, so different from Australian sands, were now mined and laced with barbed wire entanglements. The end of the famous pier was cut off, and even the promenades were partly barricaded. Only the seagulls could go where they chose. Hearing their mournful mewing David exclaimed, ‘That’s the background sound in British films! Not like our raucous squawking gulls.’

All too soon they heard another new sound. A sound which made the war seem very near indeed. An eerie wailing which made David’s spine tingle.

‘Gives you goose flesh, doesn’t it!’ he muttered to his room mate Peter Lord. It was the air-raid alert. A preliminary siren gave the first warning of approaching raiders. If the enemy planes came closer, a series of pips like radio time signals followed. But on that first occasion the German bombers were heading for London, so the welcome steady wail of the All Clear sounded soon afterwards.

Another night the raiders were closer and the men could hear distant gunfire. Then returning from the cinema one night David and Peter watched fighters going up and a German plane taking violent evasive action in the glare of searchlights. When the Bofors gun outside the hotel started firing Peter shouted ‘Watch out for your cap!’ But the blast blew their caps off. Next morning the Bofors crew claimed the plane as a definite kill.

As the Germans maintained their raids on London, David wrote in his diary, Jerry has been very persistent lately and the gunfire prevents our sleeping. Soon they got into the habit of ignoring alerts, not bothering to leave their beds. But when they saw two bombs dropping and bursting only a few hundred yards from the hotel, Peter exclaimed, ‘This is it! Down to the basement, boys!’ It was the first occasion David had taken shelter, and he wrote afterwards, I wasted no time!

The men were based at No. 11 Personnel Despatch and Reception Centre, in one of Brighton’s largest and best hotels, the Grand, on the seafront. David was pleased to be still with fellow Tasmanians Peter Lord and Ian Vickers, who had both travelled on Umgeni and been at his twenty-first birthday dinner. Ian, tall and lanky, nicknamed Skinny, had an assurance which Peter, quiet and rather shy, envied. But David appreciated the contrast and they made a good team. Their fifth-floor room had the luxury of hot and cold running water, but only standard Air Force iron bedsteads, as hotel furnishings were stored for the duration of the war. Lifts were not in use, so they challenged each other up and down the stairs. ‘This’ll keep us fit, fellas!’ Checking that blackout was

Observed in every room on all seven floors was another test of stamina.

Lectures had begun the morning after their arrival in Brighton. But if they thought they would soon be ready to go on ops, they were wrong. They still had much to learn and many months of grind, swot and slog ahead.

They also had to hand in their kit, disgusted to be issued second-hand English blankets, very inferior to their good new Australian ones.

‘Call these blankets? They’re just grey dish cloths!’ Now, instead of life jackets, gas masks had to be carried at all times. Trying them on for the first time, the men exclaimed, ‘They make us look like mini jumbos!’ ‘Mini Dumbos you mean,’ others quipped.

‘Dumbos if we don’t wear them.’

Each respirator came in a small haversack, which, minus mask and filter canister, was ideal for carrying pyjamas and shaving gear when going on leave. To ensure that the men obeyed the regulation, occasional mock attacks using actual tear gas were staged without warning. Sore and weeping eyes were enough to persuade them that carrying the mask was the best practice.

Training also focused on physical fitness, with drill sessions under a Grenadier Guards instructor. ‘Slave driver!’ David muttered. The first time the airmen were sent to the local rail station to unload steel girders and stores, they were stroppy. The second time they were even stroppier and David wrote tersely, We didn’t come 12 000 miles just to do this! But compulsory organised sport was popular and he enjoyed swimming in the local baths and playing cricket in surroundings like a village green.

At the conclusion of each day’s sessions, the men had leave from 5.00 until 11.59 pm. After exploring the historic town there was little to do. So they often went to the cinema even though most films were revivals or dealt with wartime themes. Occasionally entertainment was put on - a concert by top professional musicians and one by the RAF Band. ‘The best drummer I’ve ever heard,’ David exclaimed. Sporting fans were catered for, too, with a boxing tournament and a former champion boxer speaking about his experiences. And he used me to demonstrate his moves! David wrote home. After an inter-unit Australian Rules football match David noted in his diary, The players were rather out of practice, but improved in the second half.

On other evenings the men sat in their rooms talking or writing letters. In their first mail in over three months, David was jubilant to receive nineteen letters, and he was always diligent in responding. Writing home frequently on Australian Comforts Fund notepaper, he sometimes enclosed a weighing machine ticket to reassure his mother, as she worried that he had lost so much weight during his jaundice bout. A standard six-page airmail letter cost a shilling and threepence and took up to a month to arrive. So he often used airgraphs, which were microfilmed and sent in batches back to Australia. The delivery was speedier, but they were only one page and allowed no enclosures.

David also worked at night on assignments for the Oxford-based correspondence courses in Economics and Modern European History, in which he had enrolled.

Stationed on the rooftops of various hotels, the men watched for enemy aircraft. Gun watch was often cold

And wet and was usually uneventful. But one drizzly day at dusk, after anti-aircraft fire had downed a raider, David’s team was about to open up on a plane emerging from the mist.

‘Hold it! It’s one of ours!’ David shouted just in time. It was a salutary reminder to concentrate on the vital subject of aircraft recognition.

Out in the English Channel, invasion barges were practising amphibious operations, and aerial activity gave an opportunity to identify Spitfires, Typhoons, Mosquitoes, Mustangs, Marauders and Fortresses. On one occasion they saw over 300 allied aircraft, including American bombers, Mitchells and Bostons, heading for the continent.

‘Now the Jerries are getting as good as they gave,’ they cheered.

Watching nine Spitfires in a practice dogfight was encouraging. But seeing a German fighter shot down in flames, plummeting into the sea, was a chilling experience. Each man realised more keenly than ever before what was ahead.

‘There but for the grace of God,’ murmured one.

‘Poor devil. He was only doing his job for his country,’ David said quietly.

In a new intake of trainees, David found many of his Air Force friends and old acquaintances. One night in the hotel he was particularly pleased to find affable Alan Scott waiting for him. Alan was an old friend from Adelaide, who shared his enthusiasm for rowing, and they spent many evenings catching up. They knew each other’s families well. Alan, who had always cared for his

Alan Scott, Navigator and good friend

Widowed mother and five sisters, had appreciated holidays with David’s father, mother, and two older brothers.

‘I feel so responsible for my sisters,’ Alan said. ‘They are pretty independent, but it must be hard on women when their menfolk go to war.’

David nodded, thinking of his friend Des Hadden, who also had a widowed mother and three sisters. They

Talked optimistically of what they might do with their lives afterwards.

‘Engineering’s my scene,’ Alan said. ‘What about you? Do you want to keep flying?’

‘If I can,’ David replied. ‘I love cross-country flying. Maybe I’ll buy a second-hand Tiger Moth and stooge around Australia for a while.’

David and Alan spent a blissfully peaceful warm Sunday afternoon walking on the ‘blunt, bow-headed, whalebacked Downs’ beloved by Rudyard Kipling, lying on the close-cropped turf, overlooking green fields below, gazing up to blue autumn sky latticed with white contrails. Listening to the ‘larks at heaven’s gate’, Shakespeare’s sonnet came to life for David, and it was hard to picture the Battle of Britain that had raged above these very Downs three years earlier.

Back in Brighton they were greeted by the joyous sound of a carillon calling people to a thanksgiving service celebrating the capitulation of Italy. It was a day he would always remember.

With four days leave, David, Peter and Ian went to London. ‘Let’s catch up with other chaps from Somers at the Boomerang Club.’ Located in Australia House in The Strand, the Boomerang Club was home away from home for Australian service personnel, a popular place to meet friends, have a meal, nap on one of the big leather sofas, or read Australian news, although the papers were usually at least three months old. All branches of the services were represented in the thousand and more Australians whose shoes sank each day into the thick pink carpet of the marble-walled club. Most were airmen, including some pilots wearing the purple and white ribbon of the

Distinguished Flying Cross or Distinguished Flying Medal. There were ordinary seamen too, spruce in carefully creased bell-bottomed trousers. Officers dashingly smart with gold braid rings on well-tailored jackets, and ‘scrambled egg’ on their caps (as gold braid was irreverently known); there were even merchant seamen in tweed civvies, whose heroic efforts to bring much-needed supplies were critical to Britain’s survival.

Australian women worked cheerfully as volunteers: cooking; cutting sandwiches of grey wartime bread; serving soup, salad and snacks; making tea and coffee; washing up; and, perhaps most important of all, lending a listening ear to the homesick. They looked at family photos and dealt with emergencies like lost luggage; handed out maps, guide books and theatre tickets; assisted with travel information and arranged accommodation, which was always hard to find. A helpful woman booked beds for David, Peter and Ian at a nearby YMCA.

Next morning, David visited Kodak House in Kingsway, now RAAF Overseas Headquarters. All the mail from home was addressed here. Dedicated Australian airmen sorted and redirected the huge volume constantly arriving for all the personnel scattered on bases throughout Britain - no small task as aircrew were frequently moved. The mail was vital to maintain morale. ‘, chaps! Especially for those parcels!’

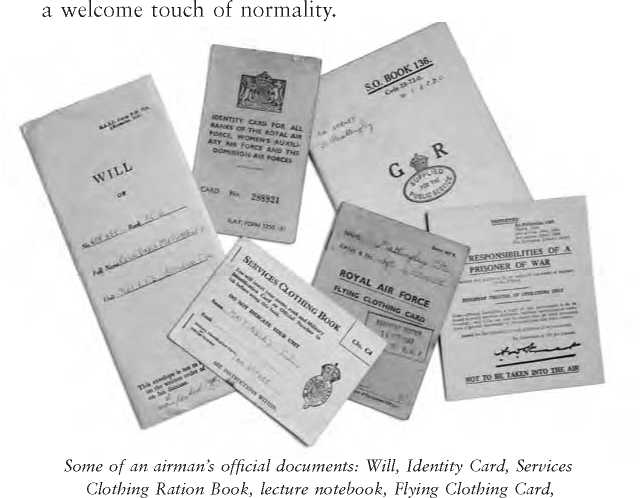

David, aware that his parents were worried about his affairs, arranged a power of attorney, in addition to the will required on enlisting. Business concluded, he set off on the expedition he had so long looked forward to - exploring London.

Wherever David went, it seemed the Germans had already

Been. He passed many skeleton buildings and bombed-out blocks. And obviously Jerry was expected again. Signs to air raid shelters were everywhere. Windows were boarded up or masked with criss-cross tape. Doorways were sandbagged. Porches held lines of red metal buckets containing sand or water, and stirrup pumps for fire extinguishing. Many razed blocks were now occupied by large water tanks, while high above the skyline barrage balloons soared on their cables like giant airborne sausages, to force enemy aircraft higher or ensnare them should they attempt a low-level raid.

But among all the changes war had brought, one wellloved feature remained the same. London Bobbies still patrolled their beats, their presence a source of comfort. Their friendly calm and willingness to give directions lent

Responsibilities of a Prisoner of War

David walked down broad Whitehall past the Cenotaph, bleak memorial to lives lost in the Great War, and from Westminster Bridge looked across the River Thames to the Houses of Parliament, even more impressive than he expected, although they had suffered bomb damage. He watched the huge hands of Big Ben, the world’s most famous clock, waiting for the chimes he had often heard on wireless and in newsreels, rapt to hear its deep tones. In Westminster Abbey, so steeped in history, he wandered for three memorable hours, pausing longest at the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior.

Next day, David and Peter went to St Paul’s Cathedral, masterpiece of renowned architect Christopher Wren, amazed its landmark dome had survived in an area so heavily blitzed. David discovered more of the London he knew from nursery rhymes which his aunt had loved to teach him - ‘London Bridge’ and ‘Oranges and Lemons’. He was glad that London Bridge had not fallen to German bombs, and sad that St Clement Dane’s church had been gutted in 1940. But its splendid ‘Oranges and Lemons’ steeple still stood proudly tall, he wrote to his parents. Let’s hope that one day it will be rebuilt in all its glory.

David and his brothers had often played Monopoly on cosy winter nights by the fire. Now he walked along Monopoly-red Fleet Street and The Strand, to see the offices of the legendary London newspaper The Times, and on past now-familiar Australia House. Making his first trip on the underground, he emerged at Piccadilly Circus, disappointed to find the famous statue of Eros boarded up. Wandering along Monopoly-yellow Piccadilly, he visited the Royal Academy’s exhibition of paintings and photos of the Allies at war. In royal-blue Park Lane

And Mayfair war had also left its mark. Elegant parks and squares had been converted into vegetable gardens, their beautiful iron fencing melted down for reuse. Green Park was a pasture for sheep. Hyde Park bristled with antiaircraft guns and temporary quarters for AA personnel.

At celebrated Speakers’ Corner, David listened to the diversity of orators who mounted their soapboxes to address the crowd. It was a vibrant gathering, orderly and good-natured, speakers jocularly dealing with interjections from persons of different opinions. He admired this society which not only tolerated but even embraced differences. He felt a wave of pride, identifying with the spirit of this great British democracy, rejoicing in this freedom of speech which was part of his heritage. So different from the repressive fascist regime they were fighting, when to voice, even to family or friends, an opinion not held by those in power could lead swiftly to arrest, imprisonment, even torture or death.

David gazed at the people standing around him in their shabby austerity clothing. Men in bowler hats stood shoulder to shoulder with others in cloth caps, their thin pale faces shadowed by lack of sleep from night after night of air raids. He was both humbled and elated to be part of them, come to help them fight the oppressors, to regain freedom for nations struggling under the Nazi jackboot.

From Marble Arch, David walked along Oxford Street, recognising department stores, like Selfridges, whose names were household words. Shortages and stringent rationing meant that most had little to display. But he lingered at a bookshop with the intriguing name of Bumpus and a tempting array of second-hand books. Red and white double-decker buses lumbering by, with

Equally intriguing destination names like Shepherd’s Bush and Elephant and Castle, lent colour to an otherwise drab scene. But on such a fine evening David continued to walk, passing Foyle’s and other famous bookshops in Charing Cross Road, until footsore but fulfilled, he finally was back at the Boomerang Club. He was part of London now and London had become part of him.

On another evening, David set out to discover places he knew from Dickens’ and Conan Doyle’s books. But as the blackout engulfed the city he became hopelessly lost. After three frustrating hours and an unfriendly encounter with a lamp post, he found his way back, only too aware that on future journeys back to base his encounters would be with much more hostile obstacles.

David and Peter then enjoyed a farm stay in Devon, with good-hearted country people pleased to welcome these young men so far from home, and glad of their able-bodied help as labour was so scarce. With fresh farm produce and rich cooking, serene days in meadow-sweet air and quiet starry nights, it was an idyllic interlude. The war seemed very far away - until they watched Liberators from a nearby base being used for searchlight practice, and knew that before long they could be pinned down in similar shafts of light over Germany, like hapless moths on a specimen sheet.

Then it was back to Brighton and the training course.

Target Dortmund

Each crew member kept silent unless addressed over the intercom by the pilot, who was concentrating on the complexity of over 100 switches, gauges, controls and dials in the cockpit. Only the wireless operator was in touch with the outside world, passing on any message to the skipper.

The Master Bomber was code-named Toby and the Main Force had the code words, more apt than usual, Press On. Their target, Dortmund, with a population of half a million, had already felt the devastating effects of previous raids. One of the most important centres of major German industry, the city was strongly defended, and the light cloud afforded little protection for the raiders.

At 17 000 feet D Dog met severe and concentrated enemy opposition. Anti-aircraft guns, both light and heavy, filled the sky with tracer, which burst on impact, and shells, which exploded at a predetermined height.

‘Jerry sure is letting us have it today!’ Boz, the mid upper gunner, thought, as from his turret he watched the fierce bursts of flak, smelling and hearing the barrage exploding perilously close on all sides. In some ways it was even more frightening by day than it had been by night. Instead of seeing quickly fading fireworks, David and his crew could see just how close together were the menacing dark puffs of smoke.

The rest of the crew listened intently to the intercom exchanges between bomb aimer and pilot and the tension was almost unbearable as D Dog ran in towards the target.

World History

World History