The Eastern Woodlands is an immense region that has been the setting for a diverse array of environments and Indian cultures. Despite the diversity, there are no convenient internal barriers that would allow us to divide the region into smaller and more easily understood areas. We are forced to look at the prehistory of the Woodlands as a single unfolding drama. There is a temptation, which has claimed too many victims, to seek a simple explanation for the complexities of the region. Eighteenth-century readers quickly accepted the idea that the prehistoric earthworks of the East were built by ‘Mound Builders’. By itself, this is a harmless concept, for it simply says that the builders of mounds were mound builders. Yet, all too soon a companion notion arose to the effect that the Mound Builders were a superior race that was wiped out and replaced by the Indians who were later encountered by European settlers. In the eighteenth century, Indian cultures were being vigorously exterminated or expelled westward ahead of the tide ot European civilization. To attribute the prehistoric monuments of the East to these cultures would have been to grant them civilization and a status approaching equality. It was an unthinkable concession, and its rejection fueled the myth of the Mound Builders.

Even in the eighteenth century convincingly sober explanations were available for the prehistoric remains that were known. In 1784, Thomas Jefferson turned his surpassing talents to the archaeology of Virginia. He had noticed burial mounds near his home, and his curiosity was aroused by the variety of local stories that circulated about them. He decided to excavate one, and he recorded his findings in detail and with accuracy. The local belief that the Indians buried their dead standing up proved to be false. What he found were ‘bundle’ burials, that is, secondary interments of disarticulated bones. He did not excavate the entire mound, but on the basis of his sample, he concluded that the structure could contain as many as a thousand such burials. He also noted that none of the remains showed signs of violent death, and that they appeared to have accumulated a few at a time. That observation should have put an end to the still popular belief that mounds were built as monuments to the assembled victims of bloody battles.

The myth of the Mound Builders spawned many offspring. The Eastern Woodlands has yielded the forged or imaginary remains of Vikings, Phoenicians, Egyptians, medieval Irish monks, Welshmen, and dozens of others over the last century. The evidence for Norsemen in North America does not appear outside Greenland and Newfoundland, as we shall see in our final chapter, and for the others there is no convincing evidence at all. When the myths are stripped away, we find that what happened over the course of 12,000 years in the Eastern Woodlands

Was an indigenous phenomenon. Sometimes influenced by Mexican developments, sometimes acting upon their own inspiration, the Indians played out a story that is indisputably American.

The eastern and southern boundaries of the region are neatly defined by the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. Elsewhere, the boundaries are not so clear. In the north, the region extends to the southern limits of the Canadian coniferous forests, a vague and uneven line that runs east to west, north of the St Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. The western boundary is a ragged line parallel to, but generally west of, the Mississippi. Here, the forests of the East give way to the grasslands of the Prairies. The Woodlands persist west of the boundary only as long tentacles following the fertile valleys of rivers that rise in the Great Plains and flow eastward to the Mississippi.

In the simplest terms, the modem Eastern Woodlands are composed of both broadleaf and coniferous trees, but there are marked differences from place to place. Hickory, oak, chestnut and other broadleaf trees flourished in the Appalachian uplands. Conifers predominated in the Atlantic and Gulf coastal lowlands. Hemlock and pine predominate over broadleaf trees in the north. It is a mosaic of subtle changes from one area to the next that is complicated by variations over time as well. Since the retreat of the last glaciers began 14,000 years ago, the forests and grasslands of the East have undergone constant change. Throughout this long period all the plants in the region produced vast quantities of tiny pollen grains, and these have been preserved in bogs and other deposits that can be accurately dated. Pollen grains from different plants can be identified and counted, and the forest cover for a given place and time can be reconstructed on paper. Thus, through the painstaking analysis of microscopic samples of pollen we are beginning to understand the changing environments that confronted prehistoric Indians.

There were no major barriers to prevent or retard the spread of prehistoric innovations within the region. Even the northward spread of agriculture after 1000 bc was slowed only by cultural conservatism, and the constant need for the selection of more rapidly maturing plant species. Farming eventually stopped at the northern fringes of the region, and has been advanced only a little farther by modern technology. As each local Indian culture adopted agriculture, it did so according to its own special traditions and environment. But the general trend was always the same, the universal human current of increasing complexity and integration, the cultural equivalent of biological evolution that we sometimes call ‘progress’.

To find the roots of the historical Indians of the Eastern Woodlands, we will reach far back into their linguistic past and try to match what we find with archaeological remains. Languages can be classified much like species of animals, and common ancestors reconstructed from clues embedded in their modern descendant forms. This is fortunate, for unlike biological species languages leave no separate fossil record. Two of the region’s three main aboriginal language families, the Iroquoian and the Algonquian-Muskogean, have probably been present in the East for 10,000 years or more. As bands slowly settled into regular seasonal movements within specific territories, linguistic subdivisions began to appear within these families. By the end of prehistory, they had fragmented into dozens of mutually unintelligible

Languages. Yet even this diversity of languages was not sufficient to prevent the relatively rapid spread of innovations, or erase common heritages. The focus of prehistoric development shifted from time to time; a given culture might lead the way during one century, only to fall behind in the next. Yet even though some localities seem to have been permanently marginal, all the prehistoric peoples of the Eastern Woodlands participated in some way in the developments discussed here.

The environmental changes that followed the retreat of the continental glaciers were not sudden or catastrophic. Children were bom and grew to old age without ever perceiving the slow and widespread evolution of their habitat. Even so, the cumulative effects were profound. By 7000 bc, most of the dominant animal species of the Ice Age were extinct in the East, or had dwindled to tiny refugee herds. The people who had depended upon these meat sources for so long gradually had to shift their attention to other kinds of food. More and more plant and animal species were utilized within each local area, and the free-roaming nomadism of the Paleo-Indians gave way to a pattern of regular seasonal movements. The Indians of this new. Archaic lifeway came to count on the availability of particular resources at particular times and places, and planned their movements accordingly. Under these conditions, chance encounters with other bands were less likely, but organized contacts increased. Regular meetings of bands could be planned into the predictable seasonal round, fostering the growth of social and economic ties that went beyond band limits. Even in the absence of agriculture and sedentary life, the cultures of the Archaic period began to form the dynamic network that would later lead to the development of extensive trade in luxury goods, and the dissemination of elaborate religious cults.

The oldest evidence for the Archaic lifeway, dating to about 8000 bc, comes from camp sites in the southern part of the Eastern Woodlands. Evidence from northern sections for this period is generally scanty or absent, despite intensive archaeological research. Large portions of the region must simply have been unoccupied for many centuries following 8000 bc. The explanation may well lie in the progression of environmental changes that followed the retreat of the last glacier. As the glacial ice melted back, the tundra along its margins and the forests that had been compressed into refuge areas began to shift northward. Unfortunately for the Indians and the animals they hunted, it was not simply a matter of moving with their environments, for the tundra and the forests were changing in character as well as location. The tundra of the Ice Age had been an ideal environment for many species; but with the retreat northward, it entered a part of the continent recently scoured by ice, where the sun comes and goes on a seasonal rather than a daily basis. Its ability to support large animal populations and the Indians who depended upon them was drastically reduced. As the result of a similar process, around 8000 bc the northern part of the Eastern Woodlands came to be dominated by spruce, fir, and pine forests, which offer little food for herbivores or carnivores, and therefore little for humans either. Thus, the development of the Archaic lifeway was primarily a southern one, and many northern areas were simply abandoned.

15

By 5000 BC, however, the silent conifer forests of the north were beginning to change as broadleaf trees became established. By 3000 bc, much of the northern section was covered with a mixed forest that attracted game animals and man. Probably most, if not all, of the Indians who moved into the northern Eastern Woodlands were ancestors of the Algonquian-speaking tribes that occupied the same territory in the colonial period. By now they had diverged substantially from their Muskogean relatives in the south, separated from them by the large block of Iroquoian-speakers in the Appalachian uplands.

Archaeological evidence indicates that it was here, in the north, that the ideological foundation for much of what followed later was laid. Mortuary practices were increasingly complex all across the Eastern Woodlands, but by 3000 bc they were particularly elaborate in the north. Although careful burials with grave offerings can be found almost anywhere, really elaborate examples are generally discovered only in sedentary and usually agricultural contexts. Perhaps these northern hunter-gatherers found stimulation in the natural richness of their environment, only recently reoccupied and still not supporting a large human population. Whatever the specific ecological and ideological forces were, we can assume that the northern mortuary complexes developed without significant external influence.

The axis of the northern Archaic developments stretches east-west through the Great Lakes, New England, and the Maritime Provinces of Canada. One of the most outstanding examples of elaborate mortuary ceremonialism in the region was once

Attributed to a mysterious race of‘Red Paint People’, so-called because the farmers who found the first burial pits were impressed by their linings of bright red hematite. Indian cemeteries of this kind, with stone tools as offerings, have since been found scattered throughout New England and the Maritimes. Red pigment, with its strong suggestion of blood and life, has been used in a similar way for thousands of years, and in many parts of the world. Here, as elsewhere, the key seems to have been the availability of the pigment in natural deposits.

The northern soils do not afford good preservation, and skeletal remains have rarely survived the millennia. Most graves contain celts (axes), adzes and gouges, often highly polished and sometimes still sharp enough to inflict a deep cut on a careless archaeologist. All three forms are heavy woodworking tools, probably designed for the construction of dugout canoes, which these fishermen and hunters of sea mammals and caribou used in their everyday activities. Other equipment included fire-rhaking kits of iron pyrite and flint, and whetstones to sharpen the edges of the woodworking tools. The finest whetstones are long slender tablets, pointed at both ends, and holed at one end for suspension. Certain graves also contain spear points ground from sheets of slate. Some are long bayonets, exquisite artifacts so slender that it is difficult to imagine how they could have survived use in the real world, or even the strains of their own manufacture. Some were skillfully faceted until they had the cross-sections of flattened hexagons, and the facets were incised with delicate geometric designs.

The cemeteries allow us to probe the ideology of these people. Here was an egalitarian society, with few favors shown according to birth, age, or sex. The dead were buried with the tools they valued most or could use most skillfully. Perhaps they needed such tools to build the spiritual boats that would take them to the next world. Like people everywhere, they perceived that journey and its end in terms of the world they already knew.

The exotic and beautiful artifacts found in graves are rarely discovered even as fragments in habitation areas. What we find in the refuse of day-to-day living are more practical and mundane implements. Perhaps the finest craftsmanship and the rarest materials were reserved for grave goods, or the prized possessions and status symbols of individuals during their lifetime, accompanying them even after death. In any case, the finest works of these ancient artisans were removed from the world of the living at a rate that nearly equalled their manufacture, a pattern of conspicuous consumption that was to continue in the East for 3500 years.

It is possible that the finest grave goods were made by specialized craftsmen, but this seems improbable. The economy of people subsisting upon hunting and gathering is unlikely to have supported craft specialists. The grave goods themselves also argue against such an interpretation. Each grave lot uncovered appears to be a special collection of unique pieces. One grave may contain a dozen slate bayonets, no two of them identical, with no artifacts of any other type. Another grave may contain only three or four finely made adze blades. It seems likely that each person produced his or her own grave goods in the course of day-to-day living, keeping them as treasured possessions even after death.

Some of the Red Paint artifacts are known not so much for the excellence of their manufacture as for the material from which they were made. Many projectile

Points are fashioned out of an attractive translucent quartzite, known to occur naturally only on the Labrador Peninsula. Notwithstanding the artistic qualities of these points, their real significance is that they provide clear evidence for the early establishment of long-distance trading in luxury goods. As we shall see, this later grew to almost continental proportions, facilitating the development of widespread prehistoric art forms and the distribution of finished pieces.

The most extraordinary Red Paint cemetery found so far is the site at Port au Choix in northern Newfoundland. The site is at the northern extremity of the area penetrated by peoples practicing the Red Paint cult. It is in an area where the closed conifer forest still predominates, 4000 years since the site was used, and thousands more since the disappearance of the last glacier. Then as now, human habitation would not have been possible without the resources of the sea.

The Port au Choix cemetery is situated on an old abandoned beach several meters above the present shore of the Gulf of St Lawrence. The beach is salted with tiny fragments of shell that have served to neutralize the normal acidity of the soil, and permit the preservation of bone and antler. Here, the skeletons of people buried 4000 years ago survive in near-perfect preservation. Some 100 individuals were unearthed, a population almost equally divided between males and females. About half were adults, the other half children. These people appear to have been healthy and robust, probably quite similar in appearance to the historical Indians of New England. Tooth wear was heavy, no doubt because hides had to be softened by chewing, and some adults had lost teeth. But tooth decay, which afflicts people with diets high in starch and sugar, was almost nonexistent. Their bone and antler artifacts have also survived, along with the more durable tools already well known from sites elsewhere. Among other things, they show us that bayonets and other fine slate artifacts had bone prototypes. The site has yielded many implements that are duplicated in both materials. Finally, Port au Choix has produced beautifully made combs, pins, effigies and other items of bone and antler that have apparently perished elsewhere. We can infer that such trinkets were widespread, but we are unlikely to find many more sites with preservation as good as at Port au Choix.

The Red Paint Indians were not the lost race that some eighteenth-century farmers thought them to be. They were among the ancestors of the historical Algonquians of the Northeast, and for fifteen centuries they supported an elaborate mortuary cult along the streams of the northern forests. This rich ceremonialism was already in decline by 1500 bc, for reasons that we are only now beginning to understand. By 500 bc, the clear ponds of the inland forests were evolving into bogs as a natural consequence of post-glacial erosion. The northeastern Woodlands seem to have lost their capacity to support human occupation. As the population thinned, and the traditional seasonal patterns became untenable, the old cult faded too. The area reverted to a cultural backwater for the remainder of prehistory.

Far to the west, at the opposite end of the northern Archaic axis, are found the remains of what has long been called the ‘Old Copper’ culture, dating from around 3000 BC. The culture takes its name from the copper objects that the Indians of the time produced. Glacial deposits near the southern shore of Lake Superior and on Isle Royale contain lumps of native copper. The prehistoric Algonquians learned how to mine and beat these ‘stones’ into useful shapes. They never developed true metallurgy, or progressed to the stage of smelting or casting. But they knew how to keep the metal from becoming brittle by annealing it, that is, by repeatedly heating the copper and plunging it into cold water, and this enabled them to fashion a much greater variety of shapes than cold hammering itself allowed. Many copper tools were modeled on earlier prototypes made of bone, stone, or other materials.

Old Copper implements include long broad spear points with long pointed tangs, short stems, or flanges for hafting. Knives are straight and pointed, or curved like the semilunar ‘woman’s knife’ of later Eskimo culture. The knife prototypes were clearly slate, whereas barbed copper harpoon points came from bone originals. Copper adzes duplicate stone examples found elsewhere. Other forms include double-ended awls and punches, always well made.

As a subtradition. Old Copper paralleled the Archaic Red Paint culture of the Northeast. Curiously, there is little to equal either of them in the lower Great Lakes area. Old Copper is restricted to the vicinity of the upper Great Lakes. It may be that something similar will yet be found in the intervening region, around Lakes Ontario and Erie. Alternatively, perhaps this area was ecologically unsuitable for earlier Archaic developments. This was certainly not the case in later periods, for the focus of the Archaic tradition shifted southward into Ohio as the exotic Red Paint and Old Copper cultures waned.

16

17

Adzes, celts, and gouges were not the only artifacts of ground and polished stone produced by Archaic cultures. The craftsmen of the time also produced beautifully made ‘boatstones’, effigy ‘birdstones’, and holed ‘bannerstones’. Their function went unrecognized for decades, but it now seems clear that all were used as weights on spear-throwers. Boatstones and birdstones were simply lashed to the wooden shafts, the latter carved to look like birds primarily for magical purposes. Bannerstones, so-called ‘winged’ objects, were attached to the shaft through a long cylindrical hole.

I6 This 14-cm-long birdstone of banded slate, about 3500 years old, would have been strapped as a weight to the flexible shaft of a spear-thrower, thus giving added spring and power to the hunter’s throw.

As we have already observed, the spear-thrower was used mainly before the introduction of the bow and arrow as a means of increasing the length of a man’s throwing arm, and therefore the velocity of his throw. Simple physics shows that the addition of a weight to a rigid spear-thrower shaft does not improve its effectiveness. The small size of the shaft hole in most bannerstones provides a clue, however. If rigid, a shaft of the size indicated by this hole would snap on the first throw. The conclusion must be that the Archaic peoples were using flexible shafts. Indeed, there is some archaeological evidence indicating that extremely tough but flexible iron-wood shafts were used with stone weights. It seems that the advantages of flexible shafts now universally recognized by golfers and fishermen were discovered and developed by Indians in North America over 7000 years ago, long before the invention of fiberglass. It would appear to be no simple coincidence that ironwood trees and spear-thrower weights have very similar distributions in North America.

Poverty Point and Olmec influences

17 Once thought to have been symbols of authority - hence their name,

‘bannerstones’ - these objects, averaging to an. in width, are now explained as spear thrower weights. Like birdstones, of similar age and function, their forms are often winged.

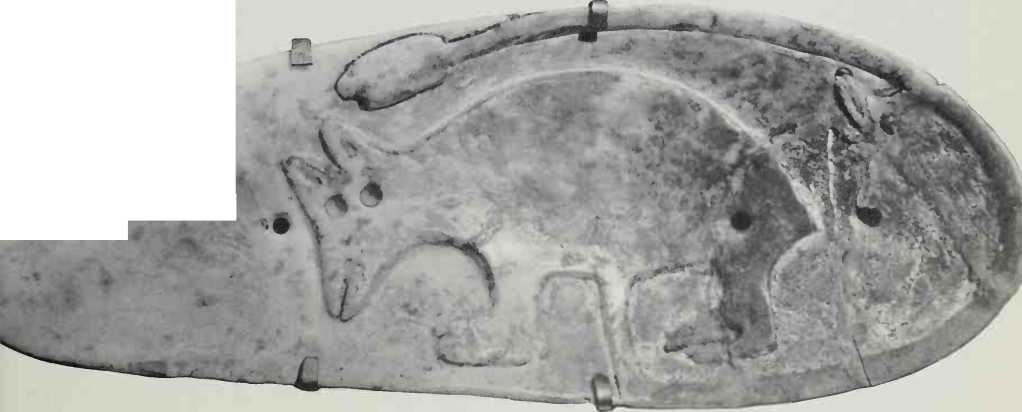

18 A strange animal, with eyes and ears askew and umbilical cord still attached, decorates this rare engraved sandal-sole gorget, 18 cm. long. Gorgets of this type, usually undecorated, were characteristic of the northern Woodlands Glacial Kame people, who often buried their dead in natural kames or hills in the centuries following 1500 BC.

The cultural center of the Eastern Woodlands in the centuries after 1500 bc was the ‘Adena’ complex of Ohio, named after the mound group and modern town of the 14 same name. The ideological basis for the new development was probably derived from the earlier mortuary cult to the northeast, but something more was added. The earthen mounds, huge when it is remembered that they were built by hand, were new to the Eastern Woodlands. The ‘Glacial Kame’ culture, which centered in southern Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana, and which flourished at about the same time as Adena, was for many years generally accepted as the innovator of burial mounds. Early burials of this culture are often found in kames (small abrupt hills) left behind by the last glaciers. Later burials are in artificial mounds. It was reasoned that the prototype burial mound was a natural kame. However, radiocarbon dating has shown that artificial Adena mounds are as old as Glacial Kame burials, suggesting that the latter were the work of country cousins trying to duplicate more elaborate Adena practices. The Glacial Kame badge was the sandal-sole gorget, an asymmetri - 18 cal tablet presumably worn around the neck. These occur in many burials of this culture, and a few of them have carved designs.

The use of glacial kames and other natural hills is known for the earlier Red Paint burials as well as for other relatively early cultures across the northern zone. Certainly this was part of the Adena heritage. But there is also evidence of a strong stimulus from Mexico, which comes in the form of a single extraordinary site that is not duplicated anywhere else in North America, the site of Poverty Point, Louisiana. 14

Poverty Point is incredibly huge. The main complex, or ‘village’, built around 1500 BC and therefore early enough to predate most of Adena, is a series of six concentric octagons nested within each other. Each is composed of eight ridges of earth about 2 meters high. The outer octagon is about 1300 meters in diameter. The inner octagons are progressively smaller, each about 100 meters less in diameter than the last. Mound A, to the west of the ‘village’, is over 20 meters high and over 200

- |fc» - *

Meters long. A long ramp descends toward the ‘village’ to the east. Another somewhat smaller mound stands to the north. A person standing on Mound A can view the vernal and autumnal equinoxes directly across the center of the ‘village’. This is the point at which the sun rises twice a year, on the first day of spring and the first day of autumn respectively.

Artifacts found at Poverty Point include most notably thousands of fired-clay balls, apparently used to boil food. Instead of preparing meals directly over open fires, the Indians would drop hot clay balls into their cooking vessels to heat up their food. Hot stones were more often used in other regions - hence the usual name given to the practice, ‘stone-boiling’. Also found arc small bird effigies and clay figurines. The latter are small human figures that bear a close resemblance to those found along the Gulf Coast of Mexico, produced by the Olmecs, the creators of the first American civilization. Poverty Point itself is reminiscent of La Venta and El Corral, both well-known Olmec sites that were occupied at about this time. It is difficult to avoid concluding that Poverty Point was a product of Olmec influence, and the gateway through which the idea of monumental architecture passed into the Eastern Woodlands.

To understand Olmec influences in the Eastern Woodlands, we must examine the origins of this early civilization. The retreat of the Canadian ice sheets and the environmental changes that ensued across the continent forced the Indians of Mexico to an early abandonment of the Paleo-Indian lifeway. The new pattern that emerged was one of intensive exploitation by hunting and gathering, an Archaic lifeway much like that of the Eastern Woodlands. The important difference was that the Mexican highlands were relatively rich in plants that had some potential as domesticates. Among them was a kind of grass that was knee high at maturity, and produced only a small stem of seeds just under a tassel at the top of the plant. Together, the seeds formed a cluster about the size of the last joint in an adult’s little finger. This, however, was wild maize, ancestral to the modern plants that sometimes produce cobs of corn the size of a man’s forearm. The Indians of highland Mexico selected this plant and others, such as beans and squash, because they could be planted with a pointed stick and tended with a hoe. Without the plow, plants that had to be sown broadcast were beyond consideration. Once under development, the crops were distributed outside their natural environments in the Mexican highlands, and into the hot humid Gulf lowlands. Here, simple slash-and-bum agricultural techniques, involving the planting of crops in the ashes of burned-down trees and shrubs, allowed heavy production along with a settled and relatively dense human population. It was on this basis that Olmec civilization began to flourish in the centuries preceding 1500 bc.

The Olmecs built clay-sided temple mounds, and mosaic pavements of serpentine blocks. Colossal heads were hewn from solid basalt, while smaller pieces were carved from Mexican jade. Pervading much of their art was the feline god motif ic which has come to be regarded as their hallmark. Sometimes drastically stylized, sometimes disarmingly natural, the art of the Olmecs was the starting point for much of the later art of prehistoric Middle America or ‘Mesoamerica’. In much the same way, later Mayan calendrics and Mesoamerican architecture can be traced back to the Olmecs. The sources of their inspiration are still obscure, but the faint trails

19 Thisjade celt represents the'were-jaguar’, mythical product oj' the union between woman and jaguar and hallmark of Obtiec cii'ilization (1500 BC-AD 100) which flourished along the Mexican Gulf Coast. Olmec arts profoundly influenced those of later Mesoamerica and the Eastern Woodlands.

Seem to lead to the Mexican highlands, Central and South America. Certainly there is no reason to presume influences from overseas. Olmec architecture, which is only superficially similar to architecture of the same age in the Old World, has many descendants, one of them Poverty Point.

Thus, the prehistory of the Eastern Woodlands after 1500 bc can be linked to Olmec civilization in Mexico. The immense architecture of Poverty Point, wedded to the ideology that already existed in the northern part of the region, gave rise to the burial-mound cults that dominate the prehistory of the Woodlands for the next 2000 years.

A conservative Archaic lifeway persisted in some areas, but by 1000 bc it had been abandoned over much of the Eastern Woodlands. In very broad terms, the new lifeway was characterized by the manufacture of pottery, burial mounds, and the beginnings of agriculture. The economy was based upon the cultivation of sunflower, goosefoot, pigweed, marsh elder, gourd, squash, and maize, the last two belonging to the maize-beans-squash trio of staple crops that, as we have seen, had been developed in Mexico over the previous millennia. Thus the Woodland Indians adopted the most suitable Mexican plants, and extended the idea of domestication to some local plants as well. What emerged was a variety of localized agricultural systems, which provided these Indians with both the stimulation and the economic capacity to embark upon a vigorous cultural florescence. Huge earthworks were built, a basketload at a time, and raw materials from great distances were transformed into artistic masterpieces. It was one of those rare periods that follow the sudden opening of new potentials, but precede the subsequent rise in population and competition for resources. For so long as that economic climate prevailed, the Indians of the Eastern Woodlands were in a golden age.

At the heart of it all was Adena culture, centered in southern Ohio and the adjacent portions of Indiana, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Over 200 Adena sites are scattered throughout the heartland. Each shows features that link it to Adena culture as a whole. Yet each also provides an idiosyncratic twist on the central theme, a theme uniformly preoccupied with death.

In southern Ohio, earthworks are both early and extensive. Like hedgerows, sharp ridges of earth define large circles, squares, and pentagons, or sometimes follow the irregular edges of flat-topped hills. The enclosed fields average about 100 meters in diameter, and seem to have been for ceremonial rather than defensive purposes, hence their common name, ‘sacred circles’. The earth from which the walls were constructed was most often taken from just inside the perimeter, giving the false impression of an interior moat. There are usually openings into the enclosures, and there are examples of two or more enclosures linked together as a single huge structure.

Adena burials might be in simple clay-lined basins, or in large log tombs built to contain one, two, or three individuals and buried under a mound. Many corpses, especially in the simpler graves, were cremated. The occupants of more elaborate tombs were apparently often smeared with red ocher or graphite, and in these cases grave goods are more frequendy present. The burial mounds occur both inside and outside the large sacred circles. Some are small, built in one stage as a tomb and monument to a single important person. Others are larger, often over twenty meters high. The mounds sometimes lie over subsurface posthole patterns that indicate that they were constructed on top of pre-existing round houses. These houses may have been ossuaries, shrines, or simply dwellings. In any case, they were usually burned down as part of the burial ceremony.

Some log tombs appear to have been provided with entrances and left open so that additional burials could be added from time to time. Once sealed, these tombs eventually collapsed under the weight of the earth above, leaving the archaeologist to reconstruct the originals through careful excavation. Except in cases of cremation, Adena burials are usually in an extended, face-up position. Occasionally an additional severed skuU was included, but it is not clear whether this belonged to a respected ancestor or an unfortunate enemy. There were further elaborations of these rites, but the important central factor is the attention given to the disposal of the dead in Adena culture. Creative energy was directed toward this apparent cult of the dead almost to the exclusion of everything else.

Although the Adena peoples made pottery, it was not the subject of much artistic elaboration, and played no role in burial ceremonialism. In fact, Adena grave goods of any sort are not common. A few impressive pieces exist, however. ‘Reel-shaped’ gorgets, usually with two perforations near the center, were made from stone tablets, often banded slate or some other attractive, fine-grained stone that takes a high polish. The tablets varied in shape from rectangles with slightly concave sides to extreme H-shaped forms. Other tablets were engraved with elaborate curvilinear designs on one or both sides, usually abstract zoomorphic motifs, most commonly a bird of prey. The uses of all these artifacts are not clearly understood. At least some of the gorgets were probably used as spear-thrower weights. The engraved tablets might have served as dye stamps for textiles, but a more likely explanation is that they were used for the application of tattoo designs. Bone awls, which would have been needed for tattooing, are often discovered with the engraved tablets, and the tablets themselves often bear grooves used to sharpen the awls.

Another important Adena artifact class is the tubular pipe. A few examples are elaborately carved, such as the famous one showing the elfigy of a standing man, a goitrous dwarf The first appearance of pipes probably marks the first appearance of tobacco in the Woodlands. All tobacco species originated in South America. The tobacco smoked by the Indians of the East appears to have arrived in North America by way of the West Indies or perhaps Mexico. The plant and smoking equipment were probably transmitted together. It is unlikely that North American Indians smoked other substances before the arrival of pipes and tobacco from the south, but they soon learned to use local plants in addition to tobacco, and sometimes in combination with it. The hardy tobacco species popular in the East eventually spread beyond the growing limits of most other important prehistoric crops, growing in areas where other domesticated plants could not grow. The English quickly adopted tobacco after 1600, but introduced a West Indian species into Virginia. It is this species, not the original hardy species, that came to be so popular with Europeans.

Other Adena artifacts include many made of native copper imported from northern Michigan. The metal was most often hammered into bracelets, beads, rings and gorgets, although there are a few copper axes. Enough tiny textile fragments have been preserved to tell us that the Adena people were accomplished in this craft too.

The Adena cult was not simply an extension of the pattern set by the Red Paint and other earlier developments. As we have seen, the emphasis in earlier centuries was upon more or less equal treatment for all the deceased, and burial with whatever prized goods each may have possessed. Adena burials, however, fall into broad classes, suggesting that now people had different standings in society, and received different burial rites accordingly. We can conclude that persons cremated in simple graves did not enjoy the same high status as those buried with offerings in log tombs. The general implication is that Adena society was not composed of small bands of equals as earlier societies had been. The comparative consideration of historically known cultures around the world suggests that Adena society was organized in lineages, groups of families linked by descent from a common ancestor. There may even have been clans, groups of linked families which could unite lineages living in different villages. Kin units of this sort often have formal leaders, and it may have been these powerful individuals who were given the most impressive burials. Alternatively, high status burial could have been accorded to persons who managed to become first among equals in a village, regardless of family connections.

Whatever specific principles may have been involved, it is apparent that Adena culture fostered the early stages of what anthropologists call ‘stratified’ society. But this does not necessarily imply the emergence of large and compact towns. The Adena people themselves appear to have been neither numerous nor territorially expansive. Their small communities were often composed of no more than four or five houses, each of which probably sheltered an extended family of closely related people. The houses themselves were circular, with a typical diameter of less than ten meters. This does not even approach the size of some historical Indian towns with their populations of hundreds or even thousands packed into communal houses. The Adena and other Eastern Woodland cultures of the time still had no plant domesticates that would provide an adequate substitute for animal protein. They avoided malnutrition by hunting and gathering wild foods to combine with their domesticates. It was a subsistence pattern that required small scattered settlements for the best use of limited wild resources.

The Adena burial cult was focused in Ohio, but its influences can be seen as far away as the Atlantic coast. Adena artifacts are found near Chesapeake Bay, and Adena burial mounds occur in New York State. These remains were once thought to have been the result of colonization by small groups moving out of Ohio. Now, however, it seems more likely that they resulted from trade contacts and the adoption of the cult by the native tribes of the coastal regions. It may be that the people of the Ohio Adena were seeking raw materials or other goods from these areas, and were able to obtain them in exchange for finished goods. The beautiful finished pieces could have stimulated interest in the cult among tribes not familiar with it, and that interest could have been further enhanced by the prospect ot obtaining more finished pieces.

Adena culture waned by about ad 200, not because of internal decadence or external catastrophe, but simply because it was in the process of becoming something else. The people did not disappear, but the complex of artifacts and burial practices that we conveniently refer to as Adena went out of fashion. At its height, Adena culture spawned a new series of developments that were to spread burial mound ceremonialism and trade in luxury items through most of the Eastern Woodlands.

These new developments are called ‘Hopewell’, a name which like ‘Adena’ derives from an Ohio mound group. The earliest such development, the Havana Hopewell, appeared in what is now Illinois by 300 bc. It may have evolved out of ‘Red Ocher’ culture, an Illinois culture not to be confused with the Red Paint culture of the Northeast, with strong influences from the Adena of Ohio. The resulting synthesis then spread back to Ohio, leading to the development of Ohio Hopewell around 100 bc, apparently while some nearby tribes still perpetuated the old Adena culture. Elsewhere, Hopewell sites developed at later dates and all flourished until about ad 550.

The rapid spread of Hopewell from one local group to another suggests that we should view it as a religious cult, rather than a whole culture. In a complex chain reaction, cultures scattered over much of the region began to interact with the Hopewell heartland, making the cult their own, and trading what they had for strange and beautiful finished artifacts. It was the logical consequence of the trends initiated by Adena.

Much of the excavation of classic Hopewell remains was carried out in the last century when antiquarianism was at its peak. Mounds were excavated in large numbers but with little care, all to the exclusion of village sites. As a result, we still know little of the daily lives of these peoples, and much important data from the mounds was lost in the excavators’ rush to acquire valuable antiquities. We are not entirely in the dark, however. We know that Hopewell mounds tended to be built in two stages. The first was usually a low construction containing a log tomb or a series of crematory basins. Later, this was usually covered by a mound of earth, sometimes twelve meters high and often more than thirty meters wide. Unlike most Adena burials, Hopewell burials were usually accompanied by lavish offerings of grave goods.

In Ohio, Hopewell mound-earthwork complexes are larger and more complicated than Adena examples. Circular, rectangular, or octagonal earthworks sometimes exceed 500 meters in diameter. Two or more may occur linked, as in some Adena cases. The internal ‘moats’ are trenches dug to provide material for the earthworks; their use as fortifications is quite improbable. Burial mounds are usually within the enclosures, as is the case at the Mound City site near Chillicothe, Ohio, which is preserved as a National Monument. Here, twenty-four mounds lie within a rectangular enclosure covering thirteen acres of land.

Another extraordinary site is Serpent Mound, southwest of Mound City. Here, an earthwork like an uncoiling serpent winds for half a kilometer along a hilltop. A hemispherical mound lies at one end, clasped in the jaws of the serpent. The other end of the monument tapers off to a tightly coiled tail. Apparently, the monument was a religious effigy that did not function primarily as a burial place.

: | |

‘ U, f '/i |

20 Serpent Mound winds for nearly half a kilometer between modern pathways on an Ohio hilltop. Built about 2000 years ago by the Adena-Hopewell peoples, earliest of the mound builders, this unique religious effigy was perhaps inspired by a comet or some other rare natural phenomenon.

21 A well-dressed tnaii of the Hopewell culture (joo BC-AD 500) wore ear-spools and pendants of beaten native copper, and pearl heads of fresh-water shellfish. The ear-spools resemble blossoms of the dogwood tree, the bark of which may have been smoked with tobacco as a mild narcotic.

Some Hopewell mounds are large structures containing hundreds of individual burials that must have taken decades to accumulate. Whether cremated or placed in log tombs, the dead were given grave goods in accordance with their status in the community. The most important persons appear to have been buried singly with large offerings under small mounds. One such burial had with it more than 135 kilograms ofimported obsidian, over half of all that found to date in Ohio Hopewell sites.

Hopewell artisans produced much of the finest prehistoric art of North America. To say that they were competent is to understate the case. They were highly skilled in working a wide variety of raw materials, imported from great distances, into an astonishing array of forms. Large amounts of native copper were imported from the southern shore of Lake Superior and beaten into cut-outs, ear-spools, artificial noses (presumably for the dead), beads, gorgets, and even panpipes. Two-dimensional drawings were sometimes embossed on sheets of copper, and thicker sheets were used as breastplates. Other nuggets were shaped into celts, axes, adzes, and awls. There is even a copper imitation of a deer-antler headdress accompanied by a pair of copper ear-spools, each beaten into the shape of a flower. The ear-spools resemble the blossoms of the dogwood tree, the inner bark of which Indians discovered to be mildly narcotic when smoked with tobacco. It seems likely that these and the headdress were part of the magical paraphernalia of a ‘shaman’, or sorcerer.

Meteoric iron was also sometimes used, usually in conjunction with copper. It was beaten into foil, and used to jacket such things as copper ear-spools, axes, adzes, and even in one case a human arm bone.

6, 22

Small nuggets of silver were imported, apparently from Ontario, and tiny amounts of gold have also been found. Cubes of galena, a lead mineral, came from the Mississippi valley. Mica was imported from the southern Appalachian area, and sheets of it were transformed into exotic cut-outs. Like the copper cut-outs, they often take the shapes of serpents, animal claws, human heads, hands, swastikas and other geometric designs. There are extraordinary examples of abstract profiles of the claws of birds of prey, and still others of long tapering human hands. The area that produced mica for Hopewell consumption also provided quartz crystal and chlorite.

Large conch shells and smaller shells were imported from Florida and the Gulf Coast. The same area provided the teeth of barracudas, sharks, and alligators, turtle shells, and the jaws of various marine fish. Grizzly bear canine teeth came from far to the west, probably the Rocky Mountains.

Hopewell artisans were also skilled knappers, and the obsidian they used was imported all the way from Yellowstone Park, Wyoming. Chert was obtained for the same purpose from closer sources in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, and a mottled chalcedony was brought in from either North Dakota or Montana. A translucent knife was chipped from quartz imported from Arkansas. All these materials were used to make knives and projectile points. Some of the tools may have been utilitarian, but many others are so large, thin, or elegant that they seem to have been designed only for show.

The utilitarian pottery of the various Hopewell cultures resembles that of Adena. Unlike Adena, however, Hopewell artisans made a series of especially fine types that appear to have been intended only as grave vessels. Some of these bear panels or zones, each decorated separately with incised lines. Various plastic techniques were used to produce an almost endless variety of decorative motifs. Hopewell potters also made copies of stone pipes and copper ear-plugs in clay. Finally, there are a few extraordinary examples of naturalistic human figurines. These are unlike any clay figurines found in Mexico or the Desert West. From these, and from the careful excavation of burials, it has been possible to show the dress and personal ornamentation of Hopewell people. Even hairstyles with elaborate braids, topknots, and shaved patches are discernible. Still, it would be a mistake to conclude that either the figurines or the more elaborate burials represent ordinary Hopewell men and women. We must conclude that the more extraordinary the find, the more extraordinary the person or persons represented. At least some of the figurines appear to represent shamans, people whose high status would have been intertwined with magical powers. One depicts a man with his hair pulled into a large knot over his forehead. The knot may in fact represent the single horn that is a shaman’s symbol in both Asia and the Americas. The wide distribution of the symbol suggests that it is a very ancient one, part of the ideological baggage of the first Americans.

Textile fragments sometimes survive next to copper ornaments, protected from decay by the copper salts. These small bits of cloth show the Hopewell to have been accomplished weavers, producing tightly woven fabrics, frequently decorated with batik-like designs.

The hand was a powerful shamanistic symbol in the cults of the Eastern Woodlands for over 2000 years. The remarkable Hopewell objects shown here probably all had ritual signifcance.

22 This hand (opposite), 25 cm. long, was cut from sheet mica; it was found buried with an Indian in Ohio, 630 km. from the nearest source of mica.

Hopewell stone-carving was as exquisite as any of their other art forms. Most notable are the platform effigy pipes, which occur as human heads, frogs, water-birds, owls, hawks, ravens, bears, and other animals. Each has a hole in its back for tobacco, and each faces the smoker, who draws the smoke through a small hole in the end of the tabular platform base. Sometimes the pipes are supplied with bowls that are not in effigy form, but are relatively plain ‘monitor’ cylinders.

There are many other examples of full-round Hopewell sculpture as well as low-relief tablet carvings more in the Adena tradition. Much of the raw material was obtained from local sources of slate, siltstone or some other hard and fine-grained rock. An especially fine pipestone called ‘catlinite’ occurs in a small area of southwestern Minnesota. Interbedded with quartzite, this stone has a bright red color and a fine grain that made it an important raw material from 300 bc on. Even after more extensive trade networks broke down, distribution of this material continued.

There are still other forms and other media. A unique eighteen-centimeter thumb was carved from cannel coal, an infrequently used material. Perhaps even rarer is the figurine made from the fossil ivory of a mammoth. Hopewell carvers were thousands of years too late to have seen such creatures alive, but like the Eskimos far to the north, they learned to use the ancient ivory to good advantage. The figurine has the same kneeling posture and general appearance as the clay Hopewell figurines, but the difference between modeling and carving is quite distinct. The comparison shows with rare clarity how the forms produced by Hopewell artisans were in part determined by the nature of the media used.

Bone, even human bone, was occasionally carved as well. One mask was made from part of a human cranium and other materials. The internal bones that formed and protected the mouth, nose, and eyes of the person while he lived were removed,

As were the entire rear and lower portions of the cranium. The carver, who we presume was also a shaman, was left with the fused bones of the upper face and forehead, which he decorated as a death mask. Such a device did not simply allow a shaman to impersonate whatever or whomever the mask represented, it allowed him to become that entity. It is a concept of transformation that is foreign and bizarre to most modern readers, but it was quite real to the shamans of prehistoric America. In these terms, the mask gives us not only a glimpse into Hopewell magic, ritual, and bone carving, but brings us face to face with death itself.

Finished examples of Hopewell artistry are occasionally found in centers of the Hopewell cult outside Ohio and Illinois. As we have seen, these centers are widely scattered in the Eastern Woodlands, and typically occur in areas where the raw material used by Hopewell artisans naturally occur. Further, styles and techniques used were so consistent over the whole region that many archaeologists conclude that each artifact type had a single point of origin. Each type may have been produced by a small group of artisans, or even a single artisan working alone, a hypothesis which is supported by the short life-spans of several types. Their dispersal over the region probably proceeded in many small steps, with desirable raw materials being traded for finished products in some cases, and for food, tobacco, and other perishable goods in others. The implication of this vast network, supported by many individual trading relationships, is that the rapid spread of the Hopewell cult did not involve wholesale migrations. Indeed, one of the surprising features of the Ohio Hopewell and other local Hopewell cultures is that they were not expansionist. This appears to have been a period of relatively peaceful coexistence. Despite the concentrations of luxury goods, political dominance of one group over another seems to have been generally absent.

The trade relationships were most probably structured as gift exchange. Intertribal trading is always a sensitive and even dangerous activity. Individuals tend to distrust members of tribes other than their own, people usually considered to have disgusting habits and heard to speak only gibberish. To overcome this natural product of ethnocentricism, and to allow the free flow of goods and materials, trading partnerships may have been established. This practice, which was widespread in North America in historical times, depended upon the formation of innumerable special bonds of friendship between pairs of persons, who in each case came from different communities. When friends from diflferent groups met, they exchanged gifts. Bargaining or even complaining was not allowed. This kind of gift exchange, as well as that associated with intertribal marriage, fostered the redistribution of goods between tribes without the danger of friction and hostility.

Exotic Hopewell trade items are not often found in village-site excavations, nor are they always associated with the dead in burials. It seems clear that these were very special goods, which functioned primarily as status items. The absence of large communities and intensive agriculture makes it likely that these goods belonged to outstanding achievers in an unranked, tribal society. Perhaps it was the kind ot social system in which each family lineage had a status that depended upon its closeness to some main line of descent. In this case, the leaders of the most prestigious lineage could expect the most lavish burials. Perhaps, as another alternative, it was a social situation in which lineages competed to validate their status by according their leaders the richest burials possible. In this case, the grand burial ceremonies would have been at once the means of both gaining and expressing high status. These explanations can all make sense in terms of the trends that Adena culture set in motion.

There is little wear on Hopewell luxury goods, suggesting that the interval between manufacture and deposition was short. The dead took their wealth and the status it represented with them, a pattern of conspicuous consumption that was good for the trade economy. Had these finished products remained in circulation, inherited by each generation from the preceding one, the need for far-flung trade would slowly have declined to a point where the demand for new raw materials would not have been great enough to sustain all the special relationships involved. Just as important, perpetuation of older goods would have ruined the market for new items and stifled the talents of artisans.

Certain raw materials were available only for relatively brief periods. For example, it appears that obsidian from Wyoming was included in Ohio Hopewell graves only between ad ioo and 200, less than twenty percent of the total time span of this Hopewell variant. When we know more about dates and the distributions of other raw materials, we may find other similarly short periods of intensive use. The lucky individual who was buried with more than half of all the obsidian known for Ohio may have broken the usual pattern and traveled the 4000 kilometers down the Ohio River, and up the Missouri and Yellowstone, in order to secure the fortune of a lifetime. This is a rare case of raw material coming from a distant region where a local expression of Hopewell never developed, and it calls for a special explanation. We can reasonably speculate that one man, probably with the support of his lineage, was responsible for the production of finished obsidian artifacts in Ohio, and that he took his unused balance with him when he died.

World History

World History