In northern China, in the middle basin of the Huanghe (or Yellow River), there arose a civilization with a whole set of characteristics of its own. Its origins are as yet not very clear, but there is no doubt that this was the cradle of Chinese civilization. A Neolithic phase characterized by habitation in villages and the growing of barley, wheat, and other cereals, was followed, again rather suddenly, around 1500 BC by a highly developed Bronze Age culture. The bronze was used for ritual kettles, gongs, bells, and vessels, as well as for arms and chariots. The latter, drawn by horses, point to contacts with the steppe regions to the west. Presumably, horses and chariots had been introduced into China by people from

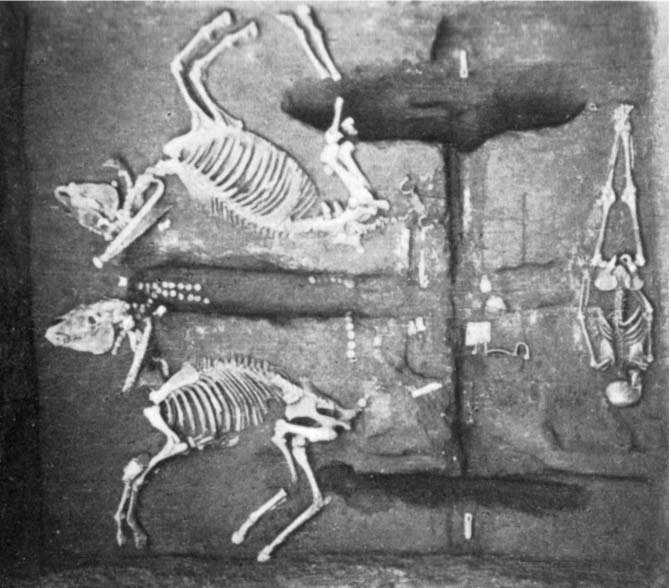

Figure 6 Chinese burial site with traces of a chariot (c. 1300 BC). A grave site with two horse skeletons, a human skeleton, and the traces of a wooden chariot, now disintegrated except for some metal fittings. This grave is part of the royal tombs near modern Anyang, where the last capital city of the Shang Dynasty was situated. The tombs are generally dated to around 1300 BC. Thus, this would be one of the earliest examples of the chariot in China—its shape seems to point to a Central Asian origin. The human skeleton would be a charioteer, sacrificed together with the horses to follow his master in death. Human sacrifice was not at all uncommon during the Shang Dynasty. Photo: Topfoto

Central Asia. The origin of bronze working, however, remains unknown but seems to have been an autonomous development rather than an importation from elsewhere. In any case, this Bronze Age culture from the start constituted an integral part of Chinese civilization. According to Chinese tradition, it was the dynasty of the Shang that ruled here from around 1500 to around 1100 BC. Their territory along the Huanghe became the base for a steady expansion of the Chinese civilization, peacefully by the cultivation of ever more stretches of land cleared from its original forests, and also by means of military conquest—a pattern that would be a feature of Chinese history for the next 3000 years.

Many ingredients of Chinese civilization were already there in the era of the Shang: foremost the town, developed as a royal residence, rectangularly laid out and walled; further, the sharp distinction within society between an elite of the larger landowners and chariot fighters around the king on the one hand, and the mass of the peasant population on the other. The latter for a long time kept its Neolithic way of life, tilling the soil in a primitive way without knowledge of the plow, whereas the use of bronze in the hands of the elite remained mainly limited to the spheres of warfare and religion. At the same time, the peasant population could always be called up to help rein in the river. For the Huanghe meanders through the northern plain and would, without human interference, constantly change its bed. Therefore, even more than in the other river basins—Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, and Indus—a massive input of labor by an obedient population was required in order to prevent calamities or restore damage by strengthening dikes or building new ones. Other factors in their turn must have contributed to what would remain the typically Chinese organization of society for a long time to come. Among these, ancestor worship should be mentioned together with the accompanying authority of the elders and the eldest in the community, and hence of those who more or less professionally maintained contact with the ancestors, like the heads of families and clans and ultimately the king himself. The worship of gods and of forces of nature also played a part here, especially where the fixed rituals of the calendar were concerned. The Chinese script also made its appearance under the Shang; originally a pictographic script, it quickly developed into a form that was the direct ancestor of the modern Chinese characters. Apparently, its use was in this period limited to religious purposes, especially oracles. In general, many achievements of Chinese civilization would for a long time remain restricted to the elites of the court and of the army—for instance, the use of silk, discovered in this period and already in its early phase developed to a high degree of technical refinement.

Toward the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the power of the Shang kings began to wane, presumably as a result of a growing independence of the larger landowners and army commanders. In Chinese tradition, the last king of the Shang is represented as a degenerate monster whose deposition by a western “duke” therefore fulfilled the will of Heaven. It was said that “the Mandate of Heaven” had passed from the Shang to a new dynasty, the Zhou, and that version of events would become the accepted explanation for every change of dynasty that henceforth was to occur in the long history of China.

World History

World History