Having conquered Europe, tobacco took on the world, expanding the arteries of global trade in the process. Portuguese ships brought it to Africa, where by 1600 it had generated a distinctive culture of pipes and rituals. They also introduced it to India, where it spread from the Mughal court at Delhi and the ports of Bengal across Asia, smoked in cheroots as well as pipes and also chewed as an addition to the betel-leaf quid. Plantations sprang up along the trade routes: the Portuguese in Gambia and the Philippines, and the Dutch in Java. Before the end of the sixteenth century Spanish traders had introduced tobacco to Japan, which developed its own style, known as kiseru: finely-shredded, mild and smoked in delicate long-stemmed pipes. But the great prize for European traders was China: a vast but tantalizingly veiled empire, a repository of huge wealth and many luxuries - pearls, porcelain, tea, silk, lacquer - that fetched fabulous prices in the West but were tightly controlled by the mandarins with whom ‘barbarian’ traders were forced to deal. The barbarians converged on China from multiple fronts - the Portuguese into Macao, the Spanish via Mexico to Manila, the Dutch from Java along the southern coast - with the commodity they hoped would prove irresistible to the imperial treasury.

An eighteenth-century Japanese courtesan smoking an elegant long-stemmed tobacco pipe. (Library of Congress, Washington, D. C.)

An eighteenth-century Japanese tobacco jar with an ivory snake entwined around a wooden skull. (Wellcome Library, London)

Though the Chinese were fiercely resistant to foreign products and habits in general, they were swift and enthusiastic converts to tobacco. Within a few decades, the problem of its foreign origins would be resolved with the assertion that it came from Fujian, the province where its use first took hold. Unlike Europe, China was a culture in which alcohol had always been problematic, partly because of a widespread genetic trait that can produce flushing reactions and intense intoxication, and partly because the disinhibition it produced was threatening to social values that stressed modesty and decorum. The paradox of a ‘sober intoxicant’ appealed to Chinese society just as it did to the new middling classes of Europe. It was first introduced in 1581 by the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci in the form oi snuff, which quickly became an elite habit, mixed with other precious substances like musk and generating a fashion for ornate snuff boxes. By the early seventeenth century smoking had begun to take hold in the south, and by 1630 it was a common sight across swathes of the coast and interior, and in port cities such as Shanghai.

The Qing dynasty of Manchus who conquered China in 1644 hac already adopted tobacco, but were alarmed at its growth among their new subjects, particularly their army, to whom they proclaimed that its use was ‘a more heinous crime even than that of neglecting archery’. They imposed a prohibition on tobacco, but this was widely ignored, and smoking continued to penetrate the public and private worlds of soldiers and intellectuals, nobles and peasants, men, women and children. Variants on the European name were replaced with coinages such as ‘smoke liquor’ or, most commonly, chi yan, ‘eating smoke’. In the absence of imperial approval it drew its sanction from medicine where, as in Europe, it was seen as ‘hot’ and ‘dry’, and a prophylactic against colds and malaria. Unlike in Europe, however, there was an existing medical culture to which tobacco smoking could be affixed: the practice of moxa, or the burning of herbs on the skin to draw out noxious humours and vapours in conditions such as rheumatism. Moxa was part of a broader medico-magical use of burning herbs and incenses to dispel unwanted influences, and tobacco benefited from the associations of smoke with purification, good luck and banishing bad spirits.

Portuguese traders in India feasting in a bathing pool, in an Indian watercolour from 1540. The Portuguese introduced tobacco to the Indian nobility, who adopted it as a luxury commodity and traded it for textiles. (Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome)

Although the American plantations continued to dominate the global trade, by the eighteenth century, tobacco was being grown across the Old World fTom West Africa to Japan, and small-scale tobacco manufactories had emerged to supply local markets. (Wellcome Library, London)

By 1700 tobacco was widespread across the entire Middle Kingdom, and the southern provinces of China were starting to adopt a new smoking mixture known as madak: tobacco mixed with a boiled solution of opium. Madak was produced by the Dutch empire in Java, where both plants were widely cultivated and traded; the Dutch had been supplying opium to China in modest quantities since the arrival of tobacco around 1630. The spread of madak was limited, but it coincided with a period of imperial instability and bureaucratic watchfulness, and provoked an edict in 1729 deploring the drug and its potential for tempting young men into smoking houses that might become hotbeds of subversive activity. The Yongzheng edict, as it was known, prohibited the importation of opium except for strictly medical uses.

But banning opium was no more effective than banning tobacco had been. By the end of the eighteenth century it was being imported in large quantities, mostly on Portuguese vessels; its price had dropped, and it was being smoked without tobacco in specially designed pipes, usually made of bamboo with silver decorations and clay bowls. These pipes reflected the fact that opium was different from tobacco: to release its intoxicating smoke, it needed to be not burnt but carefully vaporized. Small pellets of the drug, boiled with water into a treacly paste, were placed on the surface of the clay bowl with a pin, heated gently from the edges and consumed in a single inhalation. As a contraband substance, opium was not for sale in shops, but its reputation preceded it as it spread through well-established smuggler networks. The Shanghai poet Chen Cong’s Yancao Pu (‘Tobacco Manual’) of 1805 describes opium intoxication as ‘the realm of perfect happiness’.

Batavia, on the north-western tip of the island of Java, was the headquarters of the Dutch East India Company and the main entrepot for the trade in tobacco and opium across Asia. Its Town Hall still stands in the old quarter of present-day Jakarta. (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)!!

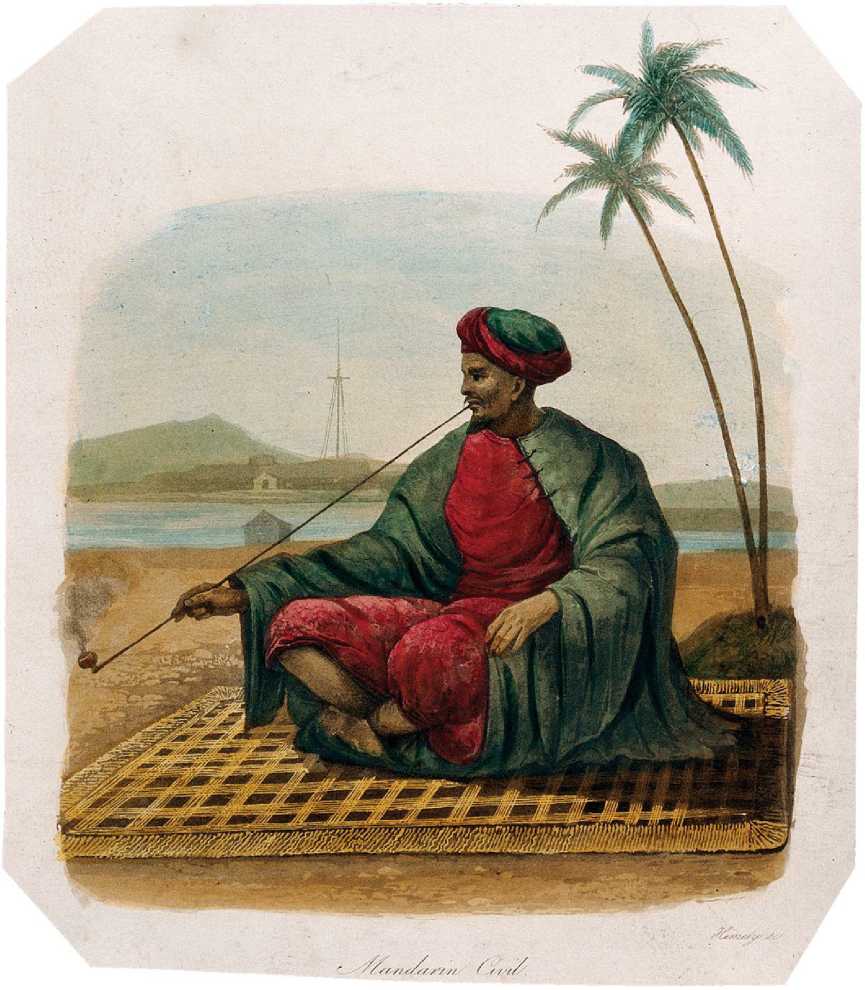

A Chinese mandarin depicted with a long-stemmed opium pipe in an aquatint from around 1820. At this point most of the opium entering China was either grown by the Portuguese in Goa or imported from Bengal by Dutch traders. (Wellcome Library, London)

Meanwhile, another drug had been making the opposite transit. Tea is native to the south-western regions of China; it had been used as a medicinal beverage for over a thousand years, and since at least the tenth century had been a staple of the Chinese and Japanese economies, with taxes to match. In 1610 the first tea shipment arrived in Europe, exported by Chinese junks to Java and then imported to Holland by the Dutch Eas' India Company. It joined the long list of coveted luxury products under Chinese monopoly control, recommended by European doctors as a cleansing tonic for liver and kidneys: the more the better, up to a hundred cups a day.

The tea habit remained an acquired and expensive taste in Europe until 1688, when the Glorious Revolution seated a Dutch monarch on the English throne. Thereafter, tea appeared more regularly and affordably in the nation’s shops, and the British East India Company started to import it directly. It proved immensely popular in England, far more so than on the European mainland, supplanting coffee at breakfast, in the home, and even in London’s thriving coffee houses. Britain’s imports grew from 200 pounds a year in 1688 to over a million by 1721, and over four million by 1750. For the East India Company who held a monopoly on the trade, and for the government who taxed it to the hilt, the national obsession was hugely profitable. Yet demand still outstripped supply, and smuggled tea invaded the market, often adulterated with local leaves - typically sloe for green tea, and hawthorn for black - and with its tannin colours approximated by toxic chemicals including Prussian blue and verdigris. By 1784 there was almost as much counterfeit tea in Britain as genuine leaf, and customs fleets were at full stretch attempting to stem the smuggling trade along the south coast. The government was forced to slash taxes from their profiteering level of 119% to a modest 12% to regain control of the market.

A tea-drinker in nineteenth-century Taiwan. The Chinese use of tea (cha) as a medicine and an aid to wakefulness dates back to the first millennium BC. It was established as a social and ceremonial beverage by the early years of the Tang Dynasty, around 700 AD. (Reproduced with the kind permission of the Director and the Board of Trustees, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond)

The British addiction to tea was now making healthy profits for importers and merchants, but it was having a ruinous effect on the national treasury. One reason for the high government taxes was that the East India Company was obliged to pay its Chinese suppliers for tea in silver, as it had few commodities for which the Chinese were interested in trading, now that tobacco was widely grown in provinces such as Yunnan.

Between 1800 and 1810, nearly a thousand tons of British silver haemorrhaged to the Chinese treasury. It was against this background that the East India Company began to take an interest in the booming market for opium around the south China coast, where a thoroughly international assortment of traders and pirates - Dutch, Armenian, Persian, Danish American, Portuguese and British - were by now supplying the illicit market. Furthermore, they were trading it directly for silver bullion.

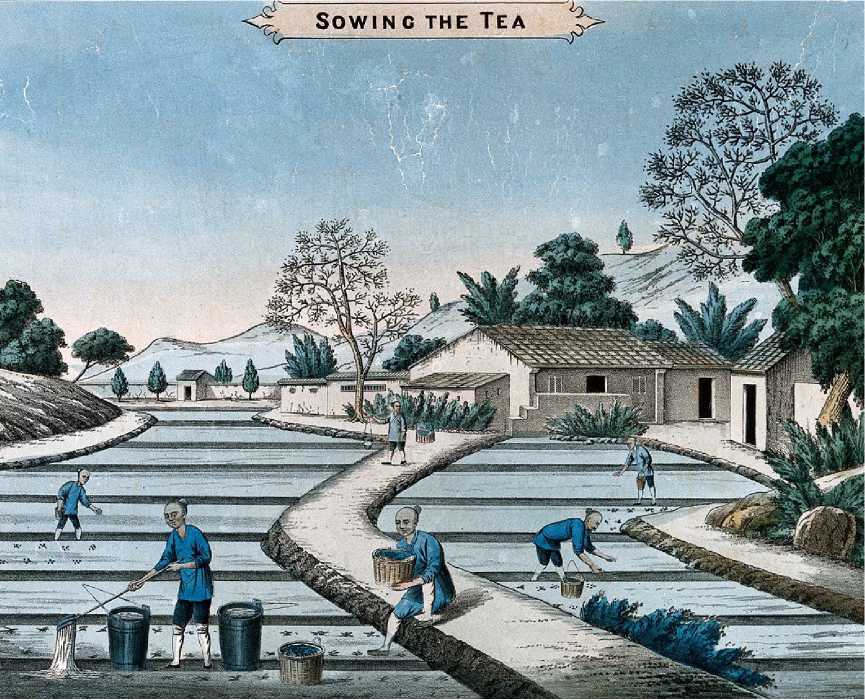

Tea produced in China for export was planted in rows, and the young leaves picked, graded and trimmed to remove the dead sections. The selected leaves were rolled into balls and dried in ovens before being packed into canisters and transported, often on rafts, to the ports where foreigners were permitted to trade. (Wellcome Library, London)

European traders discuss terms with a Chinese merchant while the tea is transferred from wicker canisters to wooden packing crates in preparation for its voyage. (V&A Images, Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The buying and selling of tea was conducted in ‘factories’, such as the one at Canton where foreigners were permitted to reside and trade under their national flags. (Peabody Essex Museum, Salem)

World History

World History