The summary of the socio-political and cultural context helps to explain the dramaturgical strategies employed in The War Over Home. Although Aristophanes’ comedy was a natural choice when it comes to a political satire against war, another important decision made was to interweave three of Aristophanes’ plots with other local plots into a multilayered, multicoloured satirical comedy. This strategy was used in order to project an image of a multilayered socio-political context and a multifaceted political-religious-cultural conflict. In contrast to the complexity of the plots, very clean-cut, clear-line/distinctions divided the characters who took part in the dramatic events. Three groups cut across the eleven scenes: the first, those advocating peace - the Jewish family (Malkizedek, Ziona and Yarden, see figure 22.3), the Palestinian family (Zahi, Nadia and Nidal), Dr Lizy Strata and her women followers (see figure 22.4); the second, those profiting from the war - Israel’s Prime Minister, his advisors and ministers, generals, settlers, the Knesset’s porter, the fishmonger

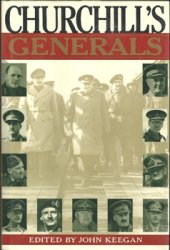

Figure 22.3 Ziona and Yarden in their house on the borderline (scene 1 The War Over Home) Photographer: Gadi Dagon. Copyright: Khan Theatre

Who, like so many poor in their ignorance, follow right-wing parties with their capitalist ideology, and Moshe, Ziona’s brother, a small war profiteer; the third group is comprised of mediators who use negotiations intended to resolve tragedies for their personal gain - in this case, the Swedish and Palestinian mediators.

The names of the characters are also significant, being symbolic of their positions regarding war and peace: Malkitzedek, a biblical name (Genesis 14.18-20 and Psalms 110.4) is constructed of two words in the manner following Aristophanes’ Dicaeopolis: ‘Melech’ (in Hebrew: king) and Tzedek (in Hebrew: justice = dike); his wife’s name, Ziona, brings to mind the ancient name for Israel - ‘Zion’ and ‘Zionism’ and their son Yarden (in Hebrew: the Jordan river). Zahi (in Arabic: to flourish, thrive, to succeed) is a peace-loving Palestinian, who before the Intifada, worked with Malkitzedek. Zahi joins Malkitzedk with his wife Nadia (in Arabic: she who assembles the people) and their son Nidal (in Arabic: a combat with weapons).

The comic movement of the sub-plots stresses the different choices taken in the transformation from war to peace and the victory of the new order: On the national and international political level, the situation only deteriorates. The fishmonger who was elected prime minister does not function differently than his predecessor; he, too, activates the army as a solution for every conflict. On the social level, the popular anti-war sex protest fails because of another woman’s stratagem: Facing Lizy

Figure 22.4 Lizy Strata and her followers demonstrating outside the Israeli parliament in The War Over Home. Photographer: Gadi Dagon. Copyright: Khan Theatre

Strata’s sex strike, the right-wing, female minister of education declares that in order to maintain the fighting strength of the army’s heroes, she is initiating an alternative movement - to provide men with free sex at any time and place! Thus only the private peace treaty promises a better future for Malkitzedek, Zahi and their families. Soon their garden flourishes with fruits and vegetables; when joined by the soldiers and the Swedish and Palestinian mediators, it blooms. Finally, as the plot develops during the nine months of Ziona’s pregnancy, it ends with a universal symbol of happiness, love, and hope - the birth of a new baby, a baby of peace.

The overall impression made by the performance was that of a carnival. Using scenic practices common to the humble vagabond tradition, ten actors played twenty multinational, cross-gender roles, including the three choruses: the generals, the women and the Settlers. The stage space changed rapidly from the public to the private sphere: the prime minister’s kitchenette, Malkizedek’s household, the gate of the knesset (Israel’s parliament) and its cafeteria, a west bank settlement, and the garden surrounding Malkitzedek’s house. In the closing scene, which takes place in Malkitzedek’s garden - the stage flourishes with green grass and roses (an idyllic space for the ideal peace) - Malkitsedk, Zahi and their families promise their spectators a better, more wonderful future.

Using Aristophanes’ dramatic strategies, the Khan’s peace project defined its socio-political goal as stimulating a change in the Israeli mentality. This strategy was meant to open audiences to a deeper reading of the political situation and to greater comprehension of the leadership’s political impotence. It was likewise aimed at preparing spectators to accept negotiations and the eventual necessary concessions. Thus, The War Over Home criticized the Israeli public for its blindness regarding the regime’s manipulation of the Jewish history of persecutions and the Holocaust, the government’s corruption, the militarism expressed in national glorification of the Israel defence forces, and its indifference to the everyday sufferings of the Palestinians. But it did more: With the aid of Aristophanes’ plots, comedy was used to focus on a fundamental aspect of Israeli individual identity - survival at all costs - and demonstrate that it is an essential human instinct, the right of every human being, superior to any nationalistic/chauvinistic ideology: Peace, in the sense of the absence of war, is of little value to someone who is dying of hunger or cold. It will not remove the pain of torture inflicted on a prisoner of conscience. It does not comfort those who have lost their loved ones in floods caused by senseless deforestation in a neighbouring country. Peace can only last where human rights are respected, where the people are fed, and where individuals and nations are free (Dalai Lama 1989).

FURTHER READING Arab-Israeli conflict

Baily 1990; Brickerton and Klausner 1998; Goldscheider 2002; Grossman 2003; Lukacs 1992.

Israeli theatre

Ben Zvi 1996. Ezraty and Solomon 2001; Levin 2003; Levy and Yaari 1998; Taube 2004; Urian 1997; 1995; Yaari 2006.

Arab-Palestinian theatre

Akad 2004; Hamdan 2006; Ibrahim 2006; Mast 2000; Masarwi 2006; Nasser 2006; Snir 1995. Kotzamani 2006; PAJ 28/2: 19-41 for a number of short articles on Arabic performance; Siam 1995.

Jerusalem (history and architecture)

Kroyanker 1994; Safdie 1989.

World History

World History