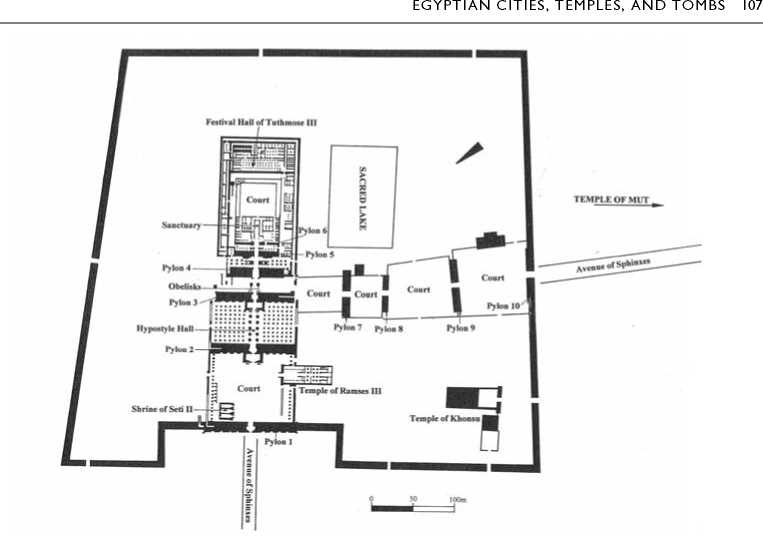

The Temple of Amun at Karnak follows the basic principles of temple layout seen at Luxor but on a much grander scale (Figure 6.8). This temple had its origins in the Middle Kingdom. Indeed, remains of the Middle Kingdom town of Thebes have been discovered in the precinct. But the temple seen today is largely the work of the New Kingdom, with important additions of the Late and Hellenistic Periods (first millennium BC). Its plan is agglutinative. The sanctuary, the residence of the god’s statue, was the key room of a temple. Once this was built, an endless succession of the other elements of a cult temple could be added: hypostyle hall, courts, and pylons. This is what happened at Karnak. It was not conceived as a unified plan; rather, a pharaoh would add a section to the existing complex, thereby increasing the size of the building. Hatshepsut was a contributor, as was Thutmose III; they were followed by many others. Some monarchs even disassembled existing shrines, reusing the blocks in new constructions, or had their names inscribed in the place of the original sponsors. The building history of the complex thus becomes difficult to unravel.

The ruins cover an area of 2ha, a large sacred precinct enclosed by a low wall that includes the Temple to Amun with its southern projection, the Sacred Lake, and various small temples.

Figure 6.8 Plan, the Temple of Amun, Karnak

Today’s visitor approaches the temple from the west along an avenue of sphinxes with ram’s heads. The major section of the temple lies on this east-west axis. The avenue leads to the first of the six pylons on this axis, the massive barriers or cross walls with doorways, sloping sides, and niches for flagpoles that mark the transitions between inner and outer spaces. The so-called First Pylon, the first entrance on the west, was the last to be built, begun perhaps during the Twenty-fifth Dynasty; it was never completed.

The first court contains two temples of the later New Kingdom, a small tripartite shrine built by Seti II to Amun, Mut, and Khonsu, and, on a north-south axis, a temple to the same triad built by Ramses III. This last is more than a chapel; it is a complete temple in itself, with court, hypostyle haU, and sanctuary.

The Second Pylon, contributed by Ramses II, included in its core a portion of the 60,000 small sandstone blocks that belonged originally to a Temple to the Aten, the sun god worshipped as the sun disk, erected here at Karnak by the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten (other blocks were found also inside the Ninth and Tenth Pylons and underneath the main Hypostyle Hall). In reaction to Akhenaten’s religious policies, Horemheb, ruling soon after, had this temple dismantled, but carefully, so the blocks could be reused. Beyond this pylon lies the great Hypostyle Hall, completed by Seti I and Ramses II, and reconstructed in this century by French archaeologists working for the Egyptian Department of Antiquities (Figure 6.9). This huge room, perhaps the most famous in all Egyptian architecture, measures 102m x 53m, with the twelve columns along the central passage rising 21m, the remaining 122 columns to the north and south rising 13m. The higher columns in the center permitted a clerestory arrangement, that is, a line of windows, which was the only source of illumination for this room. The resulting area is said to be large enough to contain the entire cathedral of Notre Dame of Paris and the column capitals broad enough that 100 people could stand on each. But the columns are thick and tightly spaced, and it is difficult to sense the overall dimensions of the space.

Such buildings devoted to the cult of the state god served also as vehicles for the recording of royal achievements. This hypostyle hall is decorated on its columns and side walls, both inside and out. The exterior walls, for example, feature episodes from the military victories of Seti I and Ramses II. If the human audience for these images was restricted, the gods were always present. Royal successes accomplished with divine support merited such commemoration on a grand scale.

Figure 6.9 Central passageway, Hypo-style Hall, Temple of Amun, Karnak

The Third Pylon, built by Amenhotep III, the patron of the Temple of Amun at Luxor, marks the beginning of the earlier Eighteenth Dynasty section of the temple. Modern exploration has revealed that this pylon, originally covered with gold and silver, contained in its fill ten dismantled shrines and temples, notably the Jubilee Pavilion for the Twelfth Dynasty pharaoh Senwosret I. Re-erected just north of the main entrance, this pavilion is the earliest building to be seen at Karnak today.

The Third Pylon is followed by the Central Court of the temple. Two pairs of obelisks originally stood here, gifts of Thutmose I, the mortal father of Hatshepsut, but only one survives in situ. By the New Kingdom, obelisks had become tall, slender poles, square in section with a pyramidal top, usually donated in pairs perhaps for symmetry, perhaps to represent the sun and the moon. They were carved from single blocks of granite, quarried near Aswan. The pink granite obelisk of Hatshepsut that still stands between Pylons 4 and 5 measures 27.5m in height and weighs an estimated 320 tons; its capstone was originally sheathed in electrum. Quarrying, transporting, and erecting such massive pieces of stone, which took seven months for these obelisks, would be an amazing triumph of engineering even today.

A second set of courts and four pylons (pylons 7—10) extends southward from this court on a north-south axis. These too date to the Eighteenth Dynasty. Pylons 7 and 8 are attributed to Thutmose III and Hatshepsut, respectively, 9 and 10 to Horemheb. In the court just north of Pylon 7, an enormous pit was discovered in 1902 which contained over 2,000 stone statues and 17,000 bronze figures, apparently a ritual clearing late in the temple’s history of the offerings left in what must have been a very cluttered temple complex. From Pylon 10 one can leave the precinct sacred to Amun and follow a sphinx-lined route southward to the Temple of Mut.

Let us instead return to the main east-west axis and the early Eighteenth Dynasty core of the temple. Pylons and courts become compressed here. Pylons 4 and 5, built by Thutmose I, enclose a small colonnade, originally roofed. Some of the drama of Eighteenth Dynasty history is attested in this small area. Hatshepsut had her pair of obelisks installed here, and removed part of the roof to do so. Their transport is depicted on the rear walls of the First Colonnade at Deir el-Bahri. Thutmose III not only replaced his aunt’s name with his own, but erected a wall around the obelisks (as high as the ceiling of the hall) to hide them instead of tearing them down.

Beyond Pylon 5 lies a second small colonnaded hall, also erected under Thutmose I, and then the last and smallest of the pylons, Pylon 6, an insertion of Thutmose III. Finally one reaches the Sanctuary for the divine boat, a typically small room, long, narrow, and dark. The statue of Amun lived here, and three times each day was washed by the high priest, dressed, perfumed, and presented with food and drink. The original boat shrine was built by Hatshepsut; its dismantled blocks have been recovered from inside Pylon 3. The present sanctuary, of pink granite, was a late remodeling of ca. 330 BC, a contribution of Philip Arrhidaeus, the half-brother of Alexander the Great. On the outside wall, south side, Philip is shown being crowned and taken in hand by the gods. Despite Philip’s Greek origin, the style of these reliefs is purely Egyptian.

Behind the Sanctuary lie an open court and the Festival Hall of Thutmose III. Of the many small rooms that lie beyond the hall, one is of particular interest, the so-called “Botanical Room,” with reliefs of exotic plants, birds, and animals brought to Egypt by Thutmose III from his campaigns in western Asia. To the south lies the Sacred Lake, 200m x 117m, fed by underground channels from the Nile. Priests purified themselves in its waters. The visitor who finds himself or herself here in the late afternoon is rewarded with a magnificent view of the ruined temple illuminated in deep golden sunlight.

World History

World History