The island of Cyprus lies in the north-east Mediterranean, cradled between Anatolia and the Levant. A stepping-stone between east and west, north and south, Cyprus has been prized by military and commercial strategists from antiquity to the present. In addition, rich copper resources provided the island with an important export commodity that supplemented the traditional agricultural base of its economy.

The city of Enkomi developed in the Late Bronze Age precisely because of these economic factors. Enkomi is located in eastern Cyprus, one of several new towns such as Kition and Hala Sultan Tekke that sprang up on the east and south coasts in the Late Bronze Age in order to profit from trade with the Levant and Egypt, now prosperous and politically stable in the empire of the New Kingdom. The ruins of Enkomi lie a few kilometers from the seacoast. Originally the city had a sheltered harbor, perhaps a navigable estuary, but erosion has filled it in and today the ruins lie high and dry, trapped in the plain. In the first millennium BC, habitation would shift to the seaside, to the city of Salamis.

The tombs of Enkomi have been known from the late nineteenth century. Identification and excavation of the city itself began with a single season of investigation in 1934 by French archaeologist Claude Schaeffer who wished to supplement his findings at Ugarit/Ras Shamra on the Syrian coast (see below). Schaeffer later resumed work in 1946. Subsequent collaborators included Porphyrios Dikaios on behalf of the Cypriot Department of Antiquities. Excavations continued intermittently until 1974 when the Turkish invasion of Cyprus led to the partition of the island, with Enkomi falling into the Turkish-controlled northern zone.

Occupation at Enkomi began in the Middle Bronze Age, but the city flourished in the Late Bronze Age. Evidence comes from archaeology, first and foremost, but we do have some information from the texts of neighboring peoples. It is generally accepted that the kingdom of Asy or Alashiya, a copper-producing country mentioned in texts beginning in the eighteenth century BC from Alalakh (near Antakya, Turkey), Mari, Egypt, and Hattusa, is in fact Cyprus. The French excavators, at least, believed Enkomi to be the capital of Alashiya; moreover, a recently discovered text from Mari speaks of “the city of Alashiya.” About Enkomi specifically and its rulers and inhabitants these texts give no information. From the Cypriots themselves we have only potential evidence, for the local Cypro-Minoan script, first attested at Enkomi ca. 1500 BC and used throughout the Late Bronze Age, has not yet been deciphered.

Enkomi grew rich as an important center for the trade in copper, the essential element in bronze, an alloy highly valued for the manufacture of tools and weapons. Cyprus had important sources of copper in the north-west part of the island, on the north and north-east slopes of the Troodos Mountains. Exploited from the Early Bronze Age into modern times, the mines are now exhausted. The ore was first collected and partially smelted before being brought to towns such as Enkomi. After further processing, the copper was formed into ingots for shipment to Syria, Egypt, and other areas without adequate metal sources. How the internal copper trade was organized we do not know; possibly a single authority oversaw mining activities, or perhaps each city took care of its own interests.

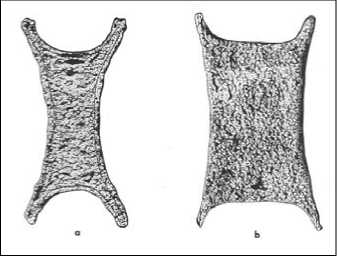

Copper (and even tin) ingots were sometimes made in the distinctive “oxhide” form, flat, thin, and roughly rectangular, with the four corners pulled out (Figure 9.1). Measurements vary from 30cm—60cm x 20cm—45cm x 4cm—6cm. Their weights range from 10kg to 37kg, with an average of 30kg. The distinctive shape, resembling an animal skin nailed in four corners for drying with its center shrunken during the process, earned these objects the picturesque name of “oxhide ingots.”

It was even proposed that these ingots represented a monetary value equivalent to that of an ox. The link with oxen has been disproved — the discovery of both four and two-handled copper ingots on the Uluburun shipwreck makes clear that the shape was designed for easy handling — but nevertheless the name has taken a firm place in the jargon of Mediterranean archaeology.

Ingots have appeared in Sardinia in the western .

° ca. 1200 BC: (a) from Serra Ilixi, Sardinia;

Mediterranean, on Crete and in the Near East, with (b) from Enkomi

Important depictions in Egyptian New Kingdom tomb paintings at Thebes. Scientific analyses of the lead isotopes and trace elements in the copper ingots have in many cases supported a Cypriot origin. The wide distribution of the ingots shows the importance of Cypriot copper resources to a very broad region. The most striking use of an oxhide ingot in Cypriot art may well be as a base for a solid bronze statuette found in an early twelfth century BC sanctuary at Enkomi. A tall (35cm), willowy bearded god protected by a horned helmet and greaves (shin guards) brandishes a shield and a spear (Figure 9.2). Because he stands on an ingot, he has been identified as the “ingot god,” the protector of the copper mines of the island. So important was he considered by the excavators that they named the Enkomi shrine after him: the Sanctuary of the Ingot God.

Figure 9.2 God standing on an ingot, bronze figurine, from Enkomi. Cyprus Museum, Nicosia

The turbulent changes that swept the eastern Mediterranean at the end of the Late Bronze Age did not spare Cyprus. Understanding exactly what happened has depended on the interpretation of pottery finds. Some pottery is imported from the Peloponnesus, according to the results of scientific analysis of the fabric, but there was also local production in the Mycenaean pictorial style, with large pots such as kraters and amphoras being favored. Such Aegean pottery types found at Enkomi, especially in tombs, have led to the conclusion that large numbers of Mycenaeans emigrated to Enkomi. In like manner, finds in eleventh-century BC contexts of Minoan types of goddess figurines with upraised arms and certain ceramics have suggested a wave of refugees from Crete arriving in Cyprus after 1100 BC. Such hypotheses that equate Aegean ceramics found on Cyprus with actual Mycenaean and Minoan settlers have been challenged in recent years. Just as in today’s America the widespread use of objects from China (to take one example) does not stem from a massive emigration of Chinese but from more complex economic relationships, so too the reasons for Aegeanizing objects on Cyprus might be quite different from the traditional explanation. As we search for the truth, we need to keep many possibilities in mind.

Other foreigners who passed through were not as benign as the possible Mycenaean and Minoan emigrants. The Sea Peoples, a loose coalition of marauders who unsuccessfully fought the Egyptians in naval battles off the Nile Delta in the late thirteenth and early twelfth centuries BC, may well have put Enkomi to the torch on two occasions when the Late Bronze Age city suffered severe damage. This pattern of destruction is attested at other Cypriot cities, notably Kition. Cypriot cities recovered and their prosperity continued during the twelfth century BC; eventually, however, the general economic decline in the eastern Mediterranean affected the island, for in the mid-eleventh century BC Enkomi was abandoned.

World History

World History