Muhammad’s campaign northward, into the Byzantine province of Arabia, in 630 was apparently planned in response to intelligence about military preparations against his coalition by some neighboring pro-Byzantine Arab tribes.8 Khalid ibn al-Walid, a tough no-nonsense soldier, led a detachment northwest to Dumat al-Jandal, an important stop on a desert trade route from southern Syria to northern Arabia, while Muhammad himself commanded the main body of men and marched directly northward. He passed by Mada’in Salih, the southern capital of the ancient Nabataean Kingdom, and reached Tabuk, an oasis in the far northwest of modern Saudi Arabia. There is no natural border between the Arabian Peninsula and the lands to the north of it; crossing from modern Saudi Arabia to Jordan, one observes no change in the scenery— the same imposing sandstone mountains, volcanic outcrops, and bleak sandy desert continue for a while as one heads northward (Figure 2.3). It was quite natural then that Muhammad, encountering no resistance at Tabuk, should continue on another 125 miles to Ayla, modern Aqaba, the northernmost port of the Red Sea, and on another 65 miles to Udhruh, very near Petra, the main capital of the Nabataean Kingdom. This was in any case the route that traders between west Arabia and southern Syria had been used to taking for many centuries now. The terms of the peace agreements Muhammad concluded with these and neighboring settlements differ considerably, suggesting that there was no collective negotiation by an agent of the Byzantine government, but rather the towns had been left to fend for themselves and the head persons of each place had to bargain as best they could.

Presumably, the Persians who had nominally occupied this region during the years 614-28 had been too busy establishing their hold over cities and

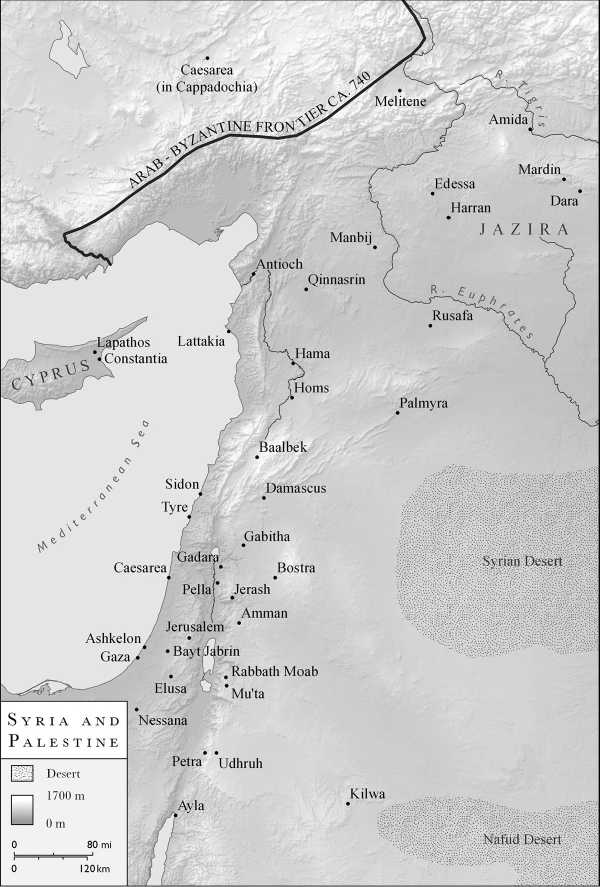

MAP 2.2 Syria, Palestine and Jazira.

FIGURE 2.3 View of scenery around Mada'in Salih, northwest Saudi Arabia. © Laila Nehme.

Extending their conquests of Byzantine lands to worry about the security of outlying areas. In such a situation it is not surprising, as contemporary evidence makes clear, that Muhammad’s followers had precursors. One chronicle records that in 610 “a band of Arabs came out of Arabia into the regions of Syria; they pillaged and laid waste many lands, committed many massacres of men and burned without compassion or pity.” A monk of Mar Saba monastery in the Judaean desert tells us that two months after the sack of Jerusalem by the Persians in 614 the monks were still unwilling to return to their monasteries in the desert “for fear of the Saracens,” and a monk from a monastery near Jericho describes the depredations of bands of “Hebrews and Saracens.” The situation was not immediately improved when the Byzantines took back control of this region, for, as one paymaster told a group of Arabs who came to claim their subsidies for keeping the desert roads safe: “The emperor can barely pay his soldiers their wages, much less you dogs!”9

Before we get into the accounts of the battles themselves, it is worth making clear that we have no good descriptions of the tactics or weaponry employed by any of the parties involved. As we said in the last chapter, the genre of Greco-Roman classicizing history, which had treated politics and warfare and was written by those who had experience in these matters, had passed away. The men who subsequently chronicled military affairs were mostly clergymen on the Christian side and storytellers and religious scholars of different sorts on the Muslim side. Their purpose in writing was to show the workings of God, not the machinations of man. Storytellers, or we might say preachers, had served in Arab armies from an early stage, encouraging the troops by recalling past glories and heroic exploits, so adding a human dimension to the bare facts. They give us an impression, for example, of the characters of the early warriors (Abu 'Ubayda as prudent, Khalid ibn al-Walid as impetuous, 'Amr ibn al-'As as wily), and of the self-image of the conquerors: “soldiers by day and monks by night,” emphasizing their passion for jihad and zuhd (simple living).10 We almost never receive from any writer, however, reliable details about troop strength and movements, specific planning, weapons deployed, layout of the site, and so on. In particular, the numbers given by our sources are very erratic, and the reader must just bear in mind that provisioning large numbers of soldiers was very difficult in the time before mechanized agriculture and transport. An army of 5,000—10,000 men is already very substantial, and 30,000—40,000 near the limit of what it is possible to sustain, especially in less fertile areas.

The first sure contemporary information that we get about the movements of the west Arabian armies comes from a chronicle that would seem, from the precision of its report, to depend on a local source. It tells us that in the year 945 of the Greeks (ad 634), “on Friday 4 February, at the ninth hour” a Byzantine force engaged “the Arabs of Muhammad” in Palestine, twelve miles east of Gaza. Nothing is said about the course of the confrontation, but it is simply noted that “the Byzantines fled, leaving behind their patrician,” whom the Arabs killed, and that “some 4000 poor villagers of Palestine were killed there, Christians, Jews and Samaritans, and the Arabs ravaged the whole region.” This would appear to correspond to an equally brief notice in Muslim sources about a battle in the spring of 634 at Dathin, described as one of the villages of Gaza, in which a general was killed.11

As the banditry continued, the governor of Palestine, based in the regional capital of Caesarea, felt that he should take action, for the Arabs were now entering the agricultural areas and nearing major settlements. He marched south toward Bayt Jabrin, which bore the grand name of Eleutheropolis, that is, “Freedom City.” However, the Arabs had prepared an ambush for him and at an opportune moment leaped out of their hiding places, screaming and shouting, and fell upon a unit of Samaritans, who unfortunately for them were at the front and faced the full brunt of the Arab onslaught; they buckled under the force of the attack and “every one of them perished by the sword.” Seeing this, the commander retreated, precipitating the hasty and disorderly flight of his men. The chronicler of this rout, though he had no Byzantine victory to boast of, managed to give a positive twist to his account by lauding the bravery of the governor, who, having fallen off his horse in the path of the pursuing Arabs, waves away his attendants, bidding them to save themselves “lest you and I shall drink the cup of death together.”12 This confrontation is probably to be equated with what Muslim sources call the Battle of Ajnadayn, which took place in July 634, since it too involved the death of a high-ranking Byzantine official.

Another encounter occurred in the vicinity of Rabbath Moab, to the east of the southern stretch of the Dead Sea. Here the austere and barren mountain range that accompanies the traveler from Arabia gives way to the more gentle and fertile highland region of the northern Jordan valley. Rabbath, renamed Areopolis by the Romans, is situated at the point of this transition and lies on the ancient road known as the Kings’ Highway, linking the cities of Ayla and Amman. The remains of a pagan temple are still visible today, but in Muhammad’s time Rabbath was a major Christian center, important enough to have its own bishop attend the council of Ephesus in ad 449. Here, then, the Arabs might have expected stiff resistance, but again they caught their opponents unawares. A contemporary source says that a Byzantine force was encamped in the vicinity and that the Arabs, “falling on them unexpectedly, put them to the sword and put to flight Theodore, brother of the emperor

Heraclius.” One might wonder that such a senior figure in the Byzantine establishment would be involved—perhaps there is confusion with an assistant of the provincial governor (vicarius) of the same name (i. e., Theodore), who was also fighting the Arabs in this region.13 However, numerous sources, Muslim ones included, do agree that Heraclius's brother was involved in an early confrontation with the Arabs and that, chastened by his defeat, he hurried back to Constantinople.

The Arabs pressed on and, taking the desert route in order to avoid major centers of settlement, they arrived at Bostra by the autumn of 634, in the south of modern Syria, just across the border from Jordan. It was a rich and prosperous city, the capital of the Byzantine province of Arabia; situated in a large fertile plain it served as an important market for pastoralists coming to sell their animal products and to buy grain, oil, wine, and manufactured goods. To the northeast rose the volcanic hills of the Hawran, in which all sorts of fruits were grown, including the grapes that provided the wine extolled in pre-Islamic Arabic poems. Christian and Muslim chroniclers are agreed that the capture of Bostra was a brief affair, for the city simply surrendered to the Arabs on the agreement that its residents' lives and property would be safeguarded in return for payment of tribute. In the sixth century there would have been a military commander based at Bostra, responsible for the troops stationed in the province of Arabia and for the overall security of that province. But it is possible that after the Persian occupation military resources were concentrated in Damascus, only sixty or so miles to the north, or at least that a new commander for Bostra was not yet in place, which would explain why the city appears not to have put up any resistance.

Contemporary chroniclers record very few clashes between Arab and Byzantine armies in this region, but other types of sources suggest that acts of despoliation and looting were common. On the other side of the river Jordan, in Jerusalem, the newly elected patriarch, Sophronius, a former monk with a passion for Greek learning and rhetoric, had strong feelings about the invaders. In the letter he wrote to mark his elevation to the headship of the Palestinian church in 634 he rails against “the Saracens who, on account of our sins, have now risen up against us unexpectedly and ravage all with cruel and feral design, with impious and godless audacity.” Later in the year the security situation was so bad that he could not travel to Bethlehem and was obliged to give his Nativity sermon in Jerusalem. As happened to the Israelites at the hands of the Philistines, he laments, “so now the army of the godless Saracens has captured the divine Bethlehem and bars our passage there, threatening slaughter and destruction.” The patriarch’s last and most detailed description of the Arab attacks appears in his sermon on the Holy Baptism, which he delivered on the feast of the Epiphany, December 6 of either 635 or 636. He urges his congregation to eschew sin, for this is the reason “why the vengeful and God-hating Saracens, the abomination of desolation clearly foretold to us by the prophets, overrun the places which are not allowed to them, plunder cities, devastate fields, burn down villages, set on fire the holy churches, overturn the sacred monasteries and oppose the Byzantine armies arrayed against them.” Of course, one cannot take such accusations at face value, since Sophronius is indulging in high rhetoric to ram home his message of repentance and abstinence from wrongdoing, but the threat was evidently real enough to make his

Sermon convincing.

Chroniclers now focus on an encounter that, in retrospect, was viewed as turning the tide against Byzantium and in favor of the Arabs: the Battle of Yarmuk. The name refers to the river that flows westward along the modern border between Jordan and Syria, and empties into the river Jordan, just south of the Sea of Galilee. The Arabs were led by two of their most famous generals: the aforementioned Khalid ibn al-Walid and Abu 'Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, who comes across as a tough but fair and pragmatic man. Both were from the prophet’s tribe of Quraysh, but whereas the former was from a clan that long opposed Muhammad, Abu 'Ubayda had been a close companion of the prophet from the very start of his mission. The emperor Heraclius had traveled to northern Syria to obtain better intelligence about events and realized that matters were serious, and so he appointed his top general in the east, the Armenian Vahan, to take charge of the operation. Heraclius was particularly worried that the key city of Damascus was under threat, and so he dispatched messengers to instruct legions with spare capacity to release some troops for the defense of the Syrian capital. Vahan marched from Antioch with the main army, apparently routing a small Arab exploratory force on the way, in the vicinity of Homs. In the early summer of 636 “an enormous multitude of Saracens set out from Arabia and headed for the region of Damascus”;15 presumably the success of the initial Arab raids had encouraged many others to join the venture. Worried by this, Vahan wrote to Theodore, a patrician of Edessa and a senior financial administrator, to bring reinforcements, and he arrived with a further 10,000 men. Once all were assembled, they encamped together, right by the bank of the river Yarmuk.

The Byzantine force looked very strong, but fortune was not on their side. An initial encounter in July 636 resulted in a defeat for the contingent of Theodore. This led to an argument between the latter and the Armenians, who subsequently proclaimed their own general emperor while abjuring Heraclius. Theodore's men withdrew and the Arabs seized the moment to attack; some had been hidden in ambush around the Byzantine camp and they now jumped out and fell upon the enemy. The Byzantines attempted to flee, but the dense mud of the flood plain bogged them down and the heat of the sun overwhelmed them. Many thousands were either cut down by the sword or slipped down the steep sides of the river valley and were either crushed or drowned. The exact details of the battle are difficult to recover, but the loss of Byzantine life was evidently considerable, for it sent shock waves around the empire, even as far away as Gaul, where one Frankish chronicler spread news of the calamity. The latter and another Latin source blame at least some of the loss of Byzantine life on an outbreak of the plague, which was raging in Syria at that time. Heraclius realized that it would be a while before more troops could be mustered and so he issued orders to all the provinces to the effect that no one should try to engage the Arabs in open combat, but everyone should instead try to maintain their positions as best they could. He himself returned to Constantinople and is prematurely portrayed by later Christian and Muslim authors as bidding Syria a sorrowful farewell, “saying sosou Syria, which means, 'rest in peace, Syria', as if he despaired of ever seeing her again.”16

This victory allowed the Arabs, as one writer put it, to “take firm possession of the provinces which they had not long since invaded, and locate their rule at Damascus, the most splendid city of Syria.” From this firm base the

Arabs were able to extend their conquests to the rest of the Levant. Christian sources speak most about three key cities: Homs, ancient Emesa and the resting place of the head of St. John the Baptist; Jerusalem, the seat of a patriarch and numerous churches and monasteries; and Caesarea, the capital of Palestine and an important port. The capture of Homs gives us an insight into why many cities seem to fall with such apparent ease to the Arabs. It had tried to hold out against a siege during the winter of 636-37 hoping that the cold would make the Arabs give up and that Heraclius would be able to raise an army to relieve them. But as the winter wore on, disputes broke out, some arguing that it would be better to surrender now when they could negotiate reasonable terms, others countering: “How can we do that when the emperor is still in authority and power?” Finally, as it became clear that help was not forthcoming, the inhabitants sued for peace and they received, like Damascus, a written covenant guaranteeing them “security for their lives, possessions, churches and laws” in return for payment of 110,000 gold coins as the tribute of the city.17 The relative fairness of the conditions of surrender encouraged many cities to submit rather than face a grueling blockade and possible slaughter, especially as they had already endured the hardship of the Persian invasion and occupation just a few years beforehand. Moreover, those cities adjacent to the Syrian desert—and that included all the settlements that submitted early on, like Bostra, Damascus, Homs, Amman, and Hama—were accustomed to dealing with Arab tribes and had relations with them on a number of different levels. They were also home to a moderate population of well-to-do and well-educated Christian Arabs, such as the Mansur family, who served as financial administrators for Heraclius in Damascus and continued to do so for the Arabs well into the eighth century.

As for Jerusalem the accounts of its capture are, as one might expect of this holiest of cities, charged with religious overtones, but they are annoyingly bereft of concrete detail. A late Christian source makes a brief reference to a two-year siege, but gives no details or clarification. Our only contemporary source reports that “the Lord’s Cross and all the vessels of the churches of God” were taken away by sea to Constantinople for safekeeping, but of military matters simply says that having requested an oath from the Arabs that they would respect life and property, the people of Jerusalem submitted to the Arabs. Otherwise Christian writers focus on two particular events. First, there is the building of a mosque on the site of the former Jewish temple, which is related by a number of contemporary and near-contemporary authors and so there is no reason to doubt it. We even have a description of it from a Gallic pilgrim, who subsequently traveled to Iona in Scotland and recounted his travels to its abbot in the 670s. He tells him that he recalls seeing in the place where Herod's Temple once stood, near the eastern wall, a rectangular “house of prayer,” which the Arabs had constructed “over some ruined remains.” It was evidently a sizable building, for it could accommodate, he says, “at least 3000 people.”18

Second, there is the visit of the caliph 'Umar I (634—44) to the holy city. This event is not reported by any early source and appears first only in a mid-eighth century chronicle, which concentrates on the meeting between 'Umar and the patriarch Sophronius. 'Umar was allegedly dressed in filthy garments of camel hair, and the patriarch, seeing this, offered him a clean loin cloth and over-garment, but 'Umar refused, only accepting in the end, after Sophronius's insistence, to wear the clean clothes for a short time until his own had been washed. There are a number of occasions in the Bible when clothes are washed or exchanged as part of a ritual of purification or investiture—such as when the high priest Joshua arrived before the angel of the Lord in dirty attire and is given new (priestly) robes in their stead (Zachariah 3:1—5)—but the exact message of the chronicler is unclear. In Muslim accounts of 'Umar's trip to Jerusalem, he is also wearing rough dress, but that is part of his image as a humble and simple man, who is wary of the trappings of civilization. Here it is Muslims urging 'Umar to put on smart clothes so that he will not appear lowly to the non-Muslims and 'Umar's refusal to do so is intended as a criticism of Muslims who covet fine attire after the fashion of the Byzantines and Persians and are seduced by earthly concerns.19

Caesarea, like all the Mediterranean coastal settlements, was much less acquainted with the Arabs than were the inland cities that bordered the Syrian desert. Its residents were more likely to be of the same doctrinal persuasion as Constantinople and the emperor, namely Chalcedonian (accepting the creed agreed upon at the council of Chalcedon in ad 451), and more likely to speak the same language, Greek, rather than Aramaic or Arabic. Moreover, as the provincial capital it had more to prove, had more to protect, and had a legion based in the city, and so would of course be expected to put up a fight. The new commander of the Arab forces in Syria, Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, recognized this challenge and so brought seventy-two siege engines, which hurled stones day and night. This went on from December 640 to May 641 until finally the massive encircling walls of the city were breached. Since the troops had obdurately refused to surrender, Mu'awiya decided to make an example of them, and all the 7,000 stationed there were killed save those who had managed to escape by boat to Asia Minor. The city was not razed, but its strongly pro-imperial ethos and the ease with which it could be supplied by sea from Constantinople meant that it was not deemed suitable by the Arabs as an administrative base. They preferred the inland cities with their closer access to the desert and their greater familiarity with Arabic and Arab tribes. Consequently, whereas many of the coastal cities declined after the Arab conquests (early Islamic Caesarea is only one tenth the size of Late Antique Caesarea), the inland cit-ies—Damascus, Bostra, Jerash, Pella, Jerusalem, and so on—all enjoyed a considerable measure of growth.20

World History

World History