Although two post-25th-Dynasty Napatan royal tombs (and some Meroitic royal tombs) are found in the cemetery to the west of Gebel Barkal, the earliest royal tombs were built in a cemetery at el-Kurru, 15 kilometers downstream from napata (Figure 9.5). George Reisner found evidence of a walled town at el-Kurru (which he never published), and Timothy Kendall has suggested that this was the earliest seat of the Kushite dynasty.

At el-Kurru reisner excavated 16 tombs which he thought were ancestral to King Piy, including tomb Ku. 8, which he identified as belonging to Piy’s predecessor Kashta. The earliest tombs (Ku. Tum. 1, 2, 4, 5) were round tumuli of stone with subterranean burial pits - reminiscent of some C-Group burials of the Second Intermediate Period. Two later tumuli, Ku. Tum. 6 and Ku. 19, had horseshoe-shaped enclosure walls built with masonry blocks. Made of mud-brick, the earliest funerary chapel appears on the east side of Ku. Tum. 6.

The ten other ancestral tombs at el-Kurru (Ku. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 20, 21, 23) had square superstructures, only two of which did not have chapels (Ku. 20 and 21). These two tombs were smaller than the others and perhaps belonged to queens or other family members of the king buried in Ku. 8, the largest of these tombs. Although Reisner thought that these ten tombs were square flat mastabas, Kendall’s investigations indicate that they were probably small pyramids.

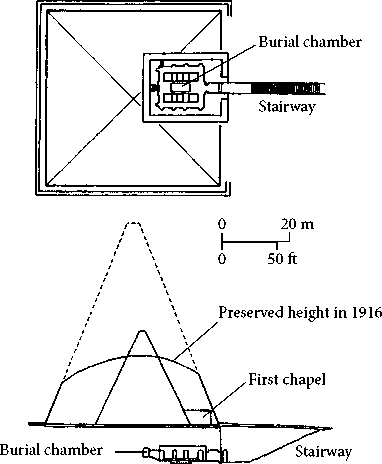

Piy’s pyramid tomb at el-Kurru (Ku. 17) represents a further elaboration of tomb design. In a 5.5-meter-deep pit, the tomb chamber was partially rock-cut with a corbel vaulted roof. It was entered by a rock-cut stairway, which was covered by a funerary chapel after the burial had taken place. The pyramid was made of solid masonry with four smooth faces.

Figure 9.5 Plan of the royal cemetery at el-Kurru. Source: Drawn by Tracy Wellman. From Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids. London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 1997, p. 195.

Map 9.2 Sites in Upper Nubia from the Third Intermediate Period onward.

Three other kings of the 25th Dynasty, Shabaqo, Shabitqo, and Tanutamani, were also buried at el-Kurru in similarly constructed monuments. But with steep sides and bases only 8-11 meters in length, the el-Kurru pyramids were very different in shape and size from the much earlier Egyptian royal tombs of the Old and Middle Kingdoms. The el-Kurru pyramids are more similar to the small pyramids over private New Kingdom tombs at Thebes.

At el-Kurru the chief queens of Piy and later kings were buried in smaller pyramid tombs on a ridge to the southwest, and minor queens were buried in separate cemeteries. Reisner also excavated a cemetery with 24 horse burials, of the four 25th-Dynasty kings who were buried at el-Kurru. The horses were found standing in four groups of pits and facing the southeast.

There is a clear evolution of tomb types at el-Kurru from indigenous-type Nubian stone tumuli, to tumuli surrounded by horseshoe-shaped enclosure walls (one with a funerary chapel), to pyramid superstructures. The Egyptianization of these tombs is also seen in the burials: the earliest ones were contracted and placed on beds (in Nubian tradition), while later ones were extended (as Egyptians were buried) and oriented east-west. With the conquest of Egypt, the Kushite royal burials emulated Egyptian ones in the treatment of the body: the body was mummified and placed in nested coffins, and the viscera were embalmed separately in canopic jars. Large numbers of Egyptian-type shawabtis were also included as tomb goods. It is likely that Egyptian and Egyptian-trained craftsmen decorated the royal tombs and made many of the artifacts that Reisner found there.

Taharqo was the first king to build his pyramid tomb in a new cemetery, Nuri, 10 kilometers upstream from Napata and on the opposite bank of the Nile (see Figure 9.6). This cemetery was used for the pyramid tombs of 21 later Napatan kings (post-25th Dynasty) to the time of Nastasen (ca. 335-315 Bc), and 53 queens, who were buried beneath considerably smaller pyramids.

With a base length of 51.75 meters, Taharqo’s pyramid is much larger than any at el-Kurru - as well as the later pyramids at Nuri. But an earlier pyramid with a base length of

28.5 meters and four smooth faces had first been built for Taharqo’s tomb. Taharqo’s later pyramid, which perhaps covered a funerary chapel to the east, was stepped in design, as were most later Kushite pyramids. Taharqo’s subterranean rock-cut tomb was also huge -21 X 16.5 meters. A narrow rectangular passage was cut around the inner rectangular tomb, which had two rows of huge rock-cut piers (more than 1 meter thick) and a low platform for the burial in the center. The tomb’s ceiling consisted of rock-cut barrel vaults.

The other kings’ tombs at Nuri had funerary chapels with a pylon faq;ade built on the southeast side of the pyramid. Up to three tomb chambers were cut 8-9 meters below ground and many were decorated with Egyptian mortuary scenes and texts. As in the later el-Kurru royal tombs, the kings’ bodies were mummified and placed in nested coffins, with the viscera in canopic jars. Evidence suggests that gold was used extensively on parts of the royal mummies, including gold masks and foil covering the fingers and toes - in a similar fashion to what Howard Carter found on Tutankhamen’s mummy. Hundreds of shawabtis were also found in these burials. Although these kings no longer controlled Egypt, they continued to be buried according to Egyptian customs for the royal dead.

In the early 4th century BC royal burials were discontinued at Nuri, as Meroe, located much farther upstream, became the place of Kushite royal burials.

Figure 9.6 Plan and cross-section of the pyramid of Taharqo at Nuri. Source: Drawn by Tracy Wellman. From Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids. London and new York: Thames & Hudson, 1997, p. 196.

World History

World History