The Neo-Babylonian city is known from ancient writers Babylonian and Greek, notably the historian Herodotus, and from modern exploration. Major excavations were conducted by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey from 1899 to 1917. Because of the high water table, Koldewey could not reach the earlier levels of Hammurabi’s town, so he had to concentrate on the NeoBabylonian plan. Apart from the Ishtar Gate, the ancient buildings were not well preserved. Already by Seleucid (Hellenistic) times baked bricks were being removed for building projects

Elsewhere. Reconstructions have been undertaken in recent decades, however, as part of excavations conducted by the Iraqi Directorate-General of Antiquities.

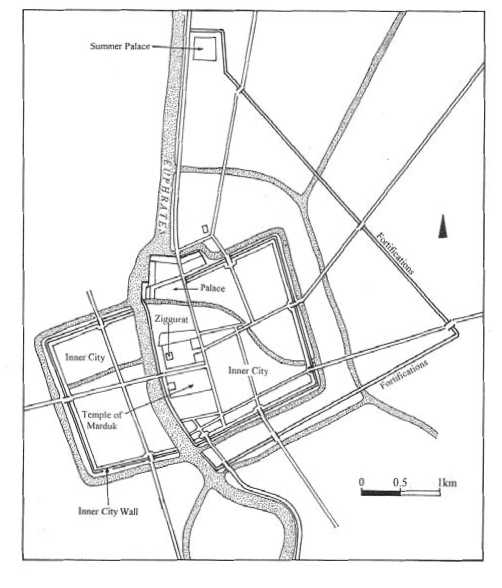

Greater Babylon covered an area of 850ha, the largest city of ancient Mesopotamia, larger than Nineveh (750ha) and far larger than Ur (60ha). Even the inner city was huge: ca. 400ha. By using the figure of 200 persons per hectare, a standard benchmark for determining urban populations in central and southern Mesopotamia, we can estimate the population of the inner city at 80,000. The city comprised two fortified sections, one inside the other, with the Euphrates, flowing north-south through the city, an important element of this defensive system (Figure 10.11). The outermost fortifications were laid out as a huge triangle, of which one side was the Euphrates itself. The other two legs stretching to the east consisted of a triple line of walls and a moat. Inside this triangle lay a rectangular core, the inner city, separately fortified. One component of this was the city center, site of the major monuments of the city: the royal palace, the cult centers, and the old residential quarter (Figure 10.12).

The rectangular core of Babylon began as a fortified square on the east bank of the Euphrates River. The area was expanded to the west bank by Nebuchadrezzar, making a total area of ca. 1.6km X 2.4km. The fortification consisted of a double line of mud brick walls, the inner measuring 6.5m in thickness, the outer 3.7m. The unfilled space between them served as a roadway. A moat was cut in front of the exterior of the walls and linked to the Euphrates, with iron gratings protecting against intruders. Baked brick set in the sealant bitumen reinforced walls in contact with the water. Bridges gave access to the eight gates into the city.

The city was laid out in a grid, with straight streets oriented toward the river. Such a regular layout was unusual for a central or southern Mesopotamian city. The names of several streets are known, listed on tablets together with the neighborhoods, the many cult places, and other topographical features. The street names are striking. Some honor the gods to whose gates the

Figure 10.12 Plan, Inner city, Babylon

Streets lead; for example, “Ishtar, intercessor for her men (people).” Other names promote morality: “Bow down, proud one!” or “Pray and he will hear you.” Some are simple: “Gemini Street” and “Narrow Street” (an alternate name for “Bow down, proud one!”).

Private houses follow traditional Mesopotamian types: two or three stories (according to ancient accounts) with a courtyard in the center. The exceptionally large size of these houses, and indeed of contemporary examples at Uruk and Ur, shows the prosperity of the region in the sixth century BC.

The city plan of Babylon differs from the typical Neo-Assyrian urban layout in restoring the main religious buildings to a place of eminence. The palaces are grandiose, to be sure. But it is the Temple of Marduk and the ziggurat, not the palace, that occupy the center of the city. The palaces stand apart, at the edges of the Inner City. In another contrast with Neo-Assyrian practice, the religious center and the palace areas are not elevated, but are located on the same flat plane as the rest of the city.

World History

World History