The naval law of Themistocles was intended as a limited defensive measure but became essential to the defense of Greece against Persia and provided the foundation for the Athenian Empire.

Date: 483 b. c.e.

Category: Law; military Locale: Athens

Summary In 483 b. c.e., Themistocles (c. 524-c. 460 b. c.e.), one of several political leaders in the recently established Athenian democracy, made a proposal to the assembly that had far-reaching implications for Athens and the whole of Greece. For many years, the Athenians had obtained silver from their state-owned mines at Laurium and frequently distributed the modest annual output as a bonus to citizens. In 483 b. c.e., however, spectacularly rich veins of silver were exposed, and a debate ensued as to the disposal of this bonanza. Many argued for the customary (if unusually large) distribution to citizens, but Themistocles proposed that the windfall be used to build two hundred warships of the advanced trireme type. His proposal carried the day, and by 480 b. c.e. Athens had a fleet that made it a major naval power in Greece. To understand how Themistocles achieved acceptance of his proposal and his rationale, one must consider the democratic constitution of Athens, its previous troubled encounters with Persia and Aegina, and changes in naval technology.

Before this buildup, Athens had a small fleet of old-fashioned pente-kontors (fifty-oared ships), which served well for coastal raids and boarding attacks on other ships but had limited effectiveness in the ramming tactics that were emerging with the spread of a newer style of warship, the trireme. With three banks of rowers per side, providing more than three times the oar power of apentekontor, the trireme had great speed and ramming power. Despite its early invention and its superiority as a ramming weapon, however, the expense of building and operating the trireme slowed its adoption. Because each ship required a skilled crew of two hundred men, the operational cost of a fleet of triremes exceeded the means of all but the wealthiest states, such as Persia, Sidon, and a few of the richest Greek city-states. The silver strike at Laurium gave Athens the opportunity to join this elite group.

In advancing his naval policy, Themistocles operated within the democratic constitution, which had been instituted by Cleisthenes of Athens in 509 b. c.e. This reform placed primary power in the hands of an assembly composed of all adult male citizens and a council of five hundred selected annually by lot, while retaining limited aristocratic features. For example, only wealthier citizens could hold the office of archon and serve on the council of the Areopagus. Pay was not provided for service on the councils or for jury duty. The new arrangement was also prone to factionalism, as rival aristocratic leaders competed for popular support. Fortunately, the system included the peculiar procedure of ostracism, whereby the Athenians might annually vote to exile one individual for ten years. Designed to preempt a revival of tyranny, it emerged in the 480’s b. c.e. as a political weapon that allowed a leader such as Themistocles to eliminate rivals and forge a consensus for a policy such as the naval law.

In proposing this costly program, Themistocles had in mind two potential threats: Aegina and Persia. Situated less than 15 miles (24 kilometers) from the Athenian harbor, the island city-state of Aegina had achieved commercial and naval power well ahead of Athens. Rivalry between the two city-states went back many years, and since at least 506 b. c.e., an undeclared state of war had existed between them, with Aegina getting the better of the conflict. Anaval expedition to avenge an Aeginetan raid on the Athenian harbor district had failed miserably and demonstrated Athenian naval inferiority. By building the new fleet, Themistocles hoped to put Athens in a position to retaliate for earlier aggressions and make the harbors of Attica safe from future Aeginetan predations. Punishment of Aegina had to wait, however, because the Persians presented a greater and more immediate threat.

In 545 b. c.e., the Persian king Cyrus the Great had conquered Asia Minor and incorporated the Greek city-states of Ionia into the Persian Empire. His successor Darius the Great (550-486 b. c.e.) asserted power across the Bosporus into European Thrace. When the Ionian city-states rebelled against Persian rule in 499 b. c.e., the Athenians alone of the mainland Greeks sent military support, an act that greatly incensed Darius. After suppressing the revolt by 494 b. c.e., he resolved to punish the Athenians for their interference. In 490 b. c.e., Darius sent an expeditionary force by sea, which landed at Marathon and suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the Athenians. Outraged at this outcome, Darius began preparations for a full-scale invasion of Greece, but his death in 486 b. c.e. forestalled this attack. His successor Xerxes I (c. 519-465 b. c.e.) took up Darius’s plan for invading Greece, and, by 483 b. c.e. (the year of the silver strike at Laurium), Persian advance forces were already in Thrace and cutting the famous canal across the Athos Peninsula that would facilitate passage of their fleet.

In proposing his naval law, Themistocles surely had this threat in mind as well as the continuing Aeginetan nuisance. Themistocles possessed the strategic insight to see the weakness of the immense Persian army: Its very size made it dependent on seaborne supplies, which were protected by the Persian navy of more than one thousand triremes. to Themistocles, when the Persian onslaught came, the Greeks had an effective naval strategy and a substantial fleet to implement it. In the decisive naval battle at Salamis in 480 b. c.e., Athenian triremes made up more than half the combined Greek fleet that defeated the larger Persian force and broke the back of Xerxes’ invasion. Ironically, the Aeginetans, who had temporarily suspended hostilities with Athens in the face of the Persian threat, were awarded the prize for valor at Salamis.

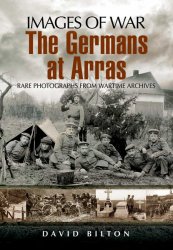

The ruins of Aegina, one of the threats to Athens that inspired Themistocles' naval law. (F. R. Niglutsch)

Once Xerxes’ invasion had been repulsed, the Athenians eagerly assumed leadership of a continuing offensive against the Persians. In 478 b. c.e., they organized the Delian League, a voluntary alliance of Aegean city-states in which members contributed either triremes or money to support the league’s common navy. In that same year, Themistocles employed a clever diplomatic ruse to secure the rebuilding of the city walls of Athens over the objections of other city-states, and he oversaw the fortification of the Athenian harbor at Piraeus. His antagonistic attitude toward Sparta led to his own ostracism around 472 b. c.e., but by this time the Athenians were committed to maintaining the navy program and pursuing the war against the Persians.

During the next two decades under Athenian command, the forces of the Delian League expelled the Persians from Greek waters and liberated the city-states of Ionia. At the same time, however, the Athenians used the fleet to coerce Greek states to join or remain in the league, which rapidly became the Athenian Empire. Aegina, the original target of Themistocles’ naval buildup, succumbed in 458 b. c.e. and became a tribute-paying member of the Delian League. That same year also saw construction on the final part of the defensive system begun by Themistocles—the famous Long Walls that linked the city of Athens with its harbor. Secure within these walls and with its commerce and imperial tribute protected by its navy, Athens now entered its greatest period of power and prosperity.

Significance The naval empire provided great material benefits to Athenians of all classes in the form of jobs, grants of land confiscated from subject city-states, and magnificent public buildings, most famously the Parthenon. It also greatly enhanced the influence of the poorest class of citizens and engendered constitutional changes that resulted in the “radical democracy” so hated by conservative critics. The security of Athens now depended less on the wealthier citizens who made up the infantry and cavalry forces than on the poorer citizens, called thetes, who rowed the triremes.

Recognition of the increased importance of the lower classes led statesmen such as Pericles to introduce reforms that further democratized the political system. Thus, the wealth qualification for the office of archon was lowered; the powers of the council of the Areopagus were drastically limited; and pay was now extended to members of the council of five hundred and to jurors. Since the aristocrats and conservative theorists who attacked

These constitutional changes clearly associated them with the rise of the

Navy, it is not surprising that they singled out Themistocles for special condemnation.

Further Reading

Jordan, Borimir. The Athenian Navy in the Classical Period. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

Morrison, John S., and J. F. Coates. The Athenian Trireme: The History and Reconstruction of an Ancient Greek Warship. 2d ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Osborne, Robin, ed. The Athenian Empire. 4th ed. London: London Association of Classical Teachers, 2000.

Plutarch. The Rise and Fall of Athens. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert. New York: Penguin Books, 1960.

Porter, Barry. “Xerxes’ Greek Campaign.” Military History 22, no. 4 (July, 2005): 22-72.

Starr, Chester G. The Influence of Sea Power on Ancient History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Strauss, Barry. The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece—and Western Civilization. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Wallinga, H. T. Xerxes’ Greek Adventure: The Naval Perspective. Boston: Brill, 2005.

James T. Chambers

See also: Athenian Empire; Athens; Cleisthenes of Athens; Government

And Law; Greco-Persian Wars; Ionian Revolt; Military History of Athens;

Navigation and Transportation; Parthenon; Pericles; Salamis, Battle of;

Technology; Themistocles; Trireme; Warfare Before Alexander; Xerxes I.

World History

World History