The Sauromatians, Sarmatians, and Alans have been differentiated archaeologically by burial artifacts and by the orientation of the deceased (Figure 4). The Soviet archaeologist B. N. Grakov defined four chronological periods for these tribes:

• Sixth to fourth century BCE - Sauromatian (type site, Blyumenfeld)

• Fourth to second century BCE - Sauro-Sarmatian (type site, Prokhorovskaya)

• Late second century BCE to second century AD - Sarmatian (type site, Suslova)

• Second to fourth century AD - Alan (type site Shipovskaya).

According to Herodotus and Hippocrates (24), the Sauromatians, who were eastern neighbors of the Scythians, spoke an earlier version of the Scythic language. The Sauromatians maintained a nomadic lifestyle independent of sedentary cultures. According to Herodotus, social statuses of Sauromatian and Early Sarmatian women were different from those

Figure 4 Reconstruction of the skull of a Sarmatian woman.

Of the Scythian women. Many of the former dressed like men, rode horses, shot bows and arrows, hunted, and took part in military campaigns.

Based on archaeological data, Soviet archaeologist K. F. Smirnov, believed that the Sauromatian culture developed from the sedentary Bronze Age Timber-Grave Culture (located in the Volga River region) and the Andronovo Culture (in the southern Ural steppes). Tribal units associated with the Sauroma-tians include the Issedones, Daha, and Massagetae. Although it is not clear where they wintered, their burials and, therefore, their summer pastures, were from the Don River to the southern Ural steppes. Before the turn of the fifth to fourth centuries, the Sauromatians in the Volga interfluvials maintained good relations with the Scythians. The balance of power soon changed in fourth century BCE as the Sauromatians pushed westward into Scythian territory along the lower reaches of the Don River.

Sauromatian westward migrations were no doubt the result of impinging eastern migrations by different ethnic but still Indo-Iranian-speaking nomads. Greek authors referred to these tribes as the Sarmatians who probably originated in the forest-steppe trans-Ural region and northwestern Kazakstan. However, recent DNA studies have revealed that certain female Sarmatians in the southern Urals, in the fourth century BCE, introduced a Mongol admixture. The Sarmatians first asserted themselves in the southern Ural steppes, continuing to move westward into the lower Volga River region and the Volga-Don inter-fluvials. Sarmatian military burials of the third to second century found deep in Scythian territory indicate that their warriors had penetrated the Scythian territory along the lower Don-Dnieper interfluvials. The campaigns of Alexander the Great also undermined the symbiotic relationship that the nomads and sedentary populations had maintained, thus creating further turmoil.

Sarmatian tribal unions mentioned in Geography of Strabo include the Rhoxolani, Aorsi, Siraki, and Yazigs. By the middle of the first century BCE, these unions had moved into the plains between the Danube and Tissa rivers as well as into the eastern Azov Sea region, the Kuban River area, and part of central pre-Caucasus. In AD 49, first an alliance and then further struggle over the Bosporus throne weakened the Siraki. Shortly thereafter this tribe as well the Aorsi disappear from written sources. Archaeological material indicates, however, that both the Siraki and the Aorsi lived in the steppes between the Don and Volga rivers until the late first century BCE.

Around the middle of the first century AD the Alans, a large nomadic union, emerged from north oF the Black Sea and conquered or assimilated the remaining Sarmatian tribes. From the mid-first century AD through most of the fourth century AD, the Alans constantly raided the trans-Caucasus and the eastern Roman provinces, keeping the sedentary populations in a constant state of terror.

Diversity in burial customs indicates that the Alans of the second to third century AD were ethnically more diverse than those of the third to fourth century AD. In the late fourth century AD when Huns from the east swept into the Alan territory, some Alanic tribes were absorbed into the Hunnic union. Others settled in the North Caucasus while other unions became a component of new ethnic confederacies of the early Middle Ages. After the Hunnic invasion, independent unions of Indo-Iranian-speaking nomads no longer existed. The north Caucasus Alans migrated into the foothills and mountains and in conjunction with indigenous tribes established the land of Alania that existed to the twelfth century AD. Other Alans settled in the Don River region intermingling with the indigenous culture. The known Alan settlements that have been excavated were both fortified and unfortified. Along with their kurgan burials, they were constructed along the Kuban River, north of the Azov Sea delta, and along the Terek River in the north Caucasus.

Sauromatian and Sarmatian Burial Rituals

Similarity in burial customs consolidated the Sauro-matian and Sarmatian tribes in the Volga region and southern Ural steppes. In addition to some diversity in burial artifacts, Sauromatian burials, oriented east, differ from those of the Sarmatians that are orientated south. Nomads were buried at summer pasture after the ground thawed, permitting them to dig deep pits and catacombs, and to construct the kurgan overmound. In the southern Ural region, where cemeteries and kurgans were closely clustered, a few very large -100+ m in diameter and known as tsar kurgans - reveal the nomadic societal hierarchy as they interred aristocracy. Because of their prominent profile against the horizon, the tsar kurgans were easily spotted from a great distance and, thus, were robbed, some shortly after the interment but many later during the Russian expansion in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The vast majority of the kurgans are relatively small, measuring from c. 1 to 30 m in diameter. Artifacts in these burials also provide insight into social rank within the society.

Although the kurgan was constructed for the primary burial, it was often reused with the secondary burials being placed laterally around the central burial. Only occasionally were multiple Sarmatian burials encountered in a single tomb. The interment could be either in a pit, often with ledges along the side and dug to a depth of ca. 2 m.; in a deep catacomb; or in a podboi, a pit with niche along the side. The deceased, probably wrapped in a felt blanket, was often further protected from the earth with organic material, such as cane or wooden planks (Figure 5).

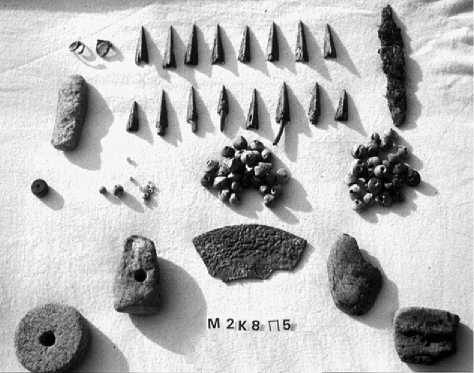

Ritual artifacts in female burials signaled a rich spiritual life, noted initially in the Sauromatian burials. The role of priestesses became increasingly important on both the clan and the tribal levels as determined by their burial accoutrements. These included zoomorphic amulets in precious metals or carved from boar’s tusks, ritual stone-carved and fired-clay altars, bronze mirrors for divinations, and fossilized seashells serving as containers for painting or tattooing. Bronze arrowheads, swords, daggers, and armor elements were provided for both male and female burials. The latter social group, female warriors, was small but was still a prominent group among Sauromatians and earliest Sarmatians (Figure 6). The earliest use of spears is also attributed to the Sarmatians.

Figure 5 Pokrovka male with child in situ.

Figure 6 Armament and cultic artifacts from an Early Sarmatian female warrior burial (Pokrovka cemetery 2, kurgan 8, burial 5).

Figure 7 Plaque from the Filippovka tsar burial in the form of fighting camels.

Plaques incorporating the ubiquitous Animal Style functioned as amuletic decoration for the bearer while diverse types of psalia (cheekpieces), bridle bits, and belt hooks provided horse accouterments. As the Sarmatian tribes become militarily stronger and acquired greater wealth, a diversity and increased value of burial offerings is noted. A large kurgan at the Filippovka Cemetery in the southern Urals yielded several secret troves containing beads, a large bronze mirror, hundreds of gold plaques, and over 20 threedimensional carved deer covered with gold and silver foil (Figure 7). In the Don River interfluvials the jewelry worn by high-status women was fashioned from gold and semiprecious stones (Figure 8).

Alan settlements as well as catacomb and podboi burials have been excavated along the Kuban and the Terek rivers. The entrance chambers to catacombs placed near the right bank of the Terek were orientated latitudinally while their chambers were placed meridionally. Grave offerings included bronze and silver fibulae, occasionally gold plaques, buckles, and arrowheads. Pottery containers are of the same shape as those of the earlier period but were wheel-thrown, often burnished, and gray fired.

World History

World History